When the praises go up, the blessings come down

It seems like blessings keep falling in my lap

From “Blessings,” Coloring Book, Chance the Rapper

As I wrote about in my last post, blessings within Judaism are not necessarily set in stone; they can and have been adapted to reflect contemporary societal and cultural needs. In this follow-up post, I mean to touch on how the very concept of what a prayer/blessing in Judaism is might also be susceptible to change.

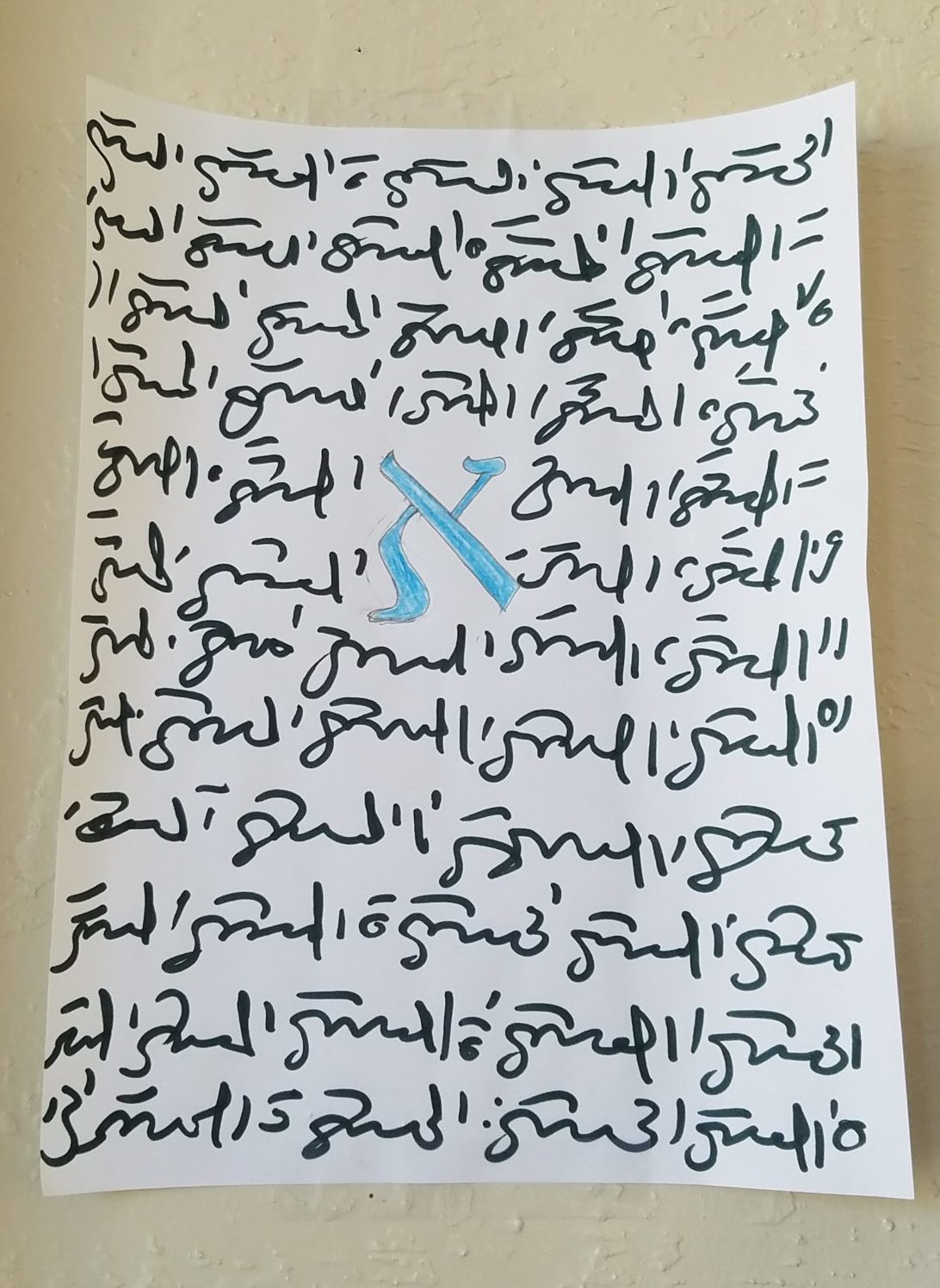

Our final exercise with Adam during our class on brachot was to write a new blessing of our own and then to find a way to illustrate it. I didn’t really write a blessing, and the illustration I went with is admittedly pretty unclear without explanation. At the center of my page I did my best to write a Hebrew Aleph—the first letter of the alphabet, unpronounced, mysterious, and central to a story by one of my favorite fiction writers, Jorge Luis Borges. All around it I scribbled in an asemic script that I’ve used to doodle with since high school. The idea behind it was that I’m interested in silence and in meaninglessness—in the tension between our observation as human beings of a senseless, chaotic universe and the search for meaning that is fundamental to our nature, and in the seeming unresponsiveness of the void. While it might seem like a bleak outlook, it is in those two places that I most readily and consistently locate my understanding of God. So I’m interested, as well, in the idea of nonverbal blessings, in prayer that is not based in language, and in the potential to connect to something higher through that. One place where I see the most potential for this is in meditation.

In his book Jewish Meditation, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan lays out the foundations for what he considers to be an indigenous Jewish meditative tradition, one that is deeply steeped in Kabbalah (a form of Jewish mysticism) and rooted, as it turns out, in prayer. For instance, Rabbi Kaplan suggests meditating on certain Hebrew phrases and Jewish prayers in a similar fashion to how one might use a mantra in Buddhist meditation practices (Kaplan 62). He also talks at length about the ecstatic prayer practices of the Chasidic movement (a Kabbalistic Orthodox sect), linking them to meditation in their ability to produce altered states of consciousness (Kaplan 48). Both meditation and prayer are capable of producing in the practitioner “altered states of consciousness,” and this forms the crux of Rabbi Kaplan’s argument that Judaism has its own indigenous meditative practice. He goes so far as to present meditation as an integral component of many biblical narratives and experiences of Jewish prophets and mystics, arguing that it is the “states of consciousness” engendered by meditative practices that we associate with the “enhanced spiritual experiences… experienced by prophets and mystics.” He claims that it is in “meditation” that “the feeling of the Divine is strengthened, and a person can experience an intense feeling of closeness to God” (Kaplan 38). To read Kaplan is to be left with the impression that, without meditation, Judaism as we understand it would not exist, and that prayer is itself a form of meditative practice already.

Rabbi Kaplan’s view on Jewish meditation is perhaps controversial. Personally, I find it problematic that he insists that Jews stick strictly to “Jewish” forms of meditation while avoiding “non-Jewish” (i.e. Buddhist and Hindu, among other traditions) forms due to an insinuated association with “idolatry.” This is problematic especially given the fact that his understanding of meditation as a white American writing in the 1980’s was clearly inflected by Western, appropriated understandings of Eastern traditions. Nonetheless, his writings on the topic open up an interesting dialogue on the relationship between saying blessings and sitting for meditation, and on the shared goals of both practices.

Why do we pray? During a session with Rabbi Dev Noily from Kehilla in Oakland, we learned of four basic types of prayers that people make: prayers of gratitude, prayers to make request, prayers asking for forgiveness, and prayers expressing awe. During our class back in June, Adam presented saying blessings as a way to slow down, be mindful, and check in with ourselves and the universe. Clearly, Adam and Rabbi Dev approach the topic of prayer from different directions, but I think there are ways to map one answer onto the other. After all, what’s the point of articulating one’s gratitude and/or awe if not to slow down and take a moment? Can’t we see the goal of “checking in” as being articulated by the idea of evaluating one’s needs and regrets, a way of evaluating our particular position in the nexus of space-time? Can’t we see meditation as fulfilling similar purposes?

When I think about meditation and the ways or reasons why I’ve integrated mindfulness practice into my life, I often frame it as a way of getting to better know my thoughts and mental landscape while also working towards the goal of transcending ego and connecting with a greater presence. As I’ve come to understand prayer through my experiences here, I see it in a similar way. Another aspect linking prayer and meditation is their relationships to tradition and community, both practices coming with their own long histories and an intrinsic quality of linking their practitioners to each other in a certain communal bond. In speaking and saying blessings (as well as meditating) with my cohort here at Urban Adamah, I’ve felt firsthand the power of these practices to unite groups and orient individuals within lineages of practitioners. Observing these common aspects shared by meditation and prayer, it strikes me that they’re not the only activities that I engage in that fulfill these needs, and it makes me wonder about the broad swathe of activities that could be potentially subsumed into the category of “blessings.” Two that seem particularly salient given my experiences here are physical work (farming) and activism.

Runners often talk about their “runners’ highs.” I’ve tried (and stopped trying) to be a runner. But for a while during my undergraduate career, I did work down in the stacks at UVA’s Special Collections Library, where most of my day consisted of being on my feet performing repetitive tasks such as putting books away in order on shelves or working with my hands to make cases to help preserve precious items. Nowadays, I’m a farmer, which, while intellectually engaging, also involves a lot of rote, physical tasks. In both cases, I’ve experienced the pleasure of losing myself in mechanical tasks, and the reward of connecting with something bigger than myself. At the Special Collections Library, that thing was history; at Urban Adamah, that thing is the Earth. In both cases, these experiences have helped me to better understand the way that I am constituted and the position I take within the world. Similarly, activism for me has involved a lot of repetitive action (marching and chanting for hours, sitting through long and frustrating meetings that go in circles, learning and unlearning and challenging my perceptions) that have, in certain moments, brought me to elevated heights, helped me to feel more connected to my community, and better understand myself as a body navigating society and a subjectivity existing within the context of history. Perhaps this is too liberal an application of the concept of prayer, but I tend not to shy away from being too far to the left on any issue. I believe that prayer can be a lot of things, and that language is only the beginning.