Reflection on Kierkegaard in The Age of the American Strong Man

By Charles Marsh | December 12, 2025

“I would say that he who has learned rightly to be anxious has learned the most important thing.”

-Søren Kierkegaard

Every age invents its own vocabulary for fear. In Don DeLillo’s novel White Noise, a black cloud drifts toward a Midwestern town in what DeLillo calls the Airborne Toxic Event. It moves with the wind, swollen and restless, a shape beyond naming—as if dread had itself become a quality of the weather. More recently, climate psychologist Brit Wray gave the title Generation Dread to her study of the uneasy emotional signature of our time. Those born into a warming planet enter a world freighted with fear, sadness, anger, and guilt.

Few have exploited the national psyche more skillfully than the current president. His political life is a constant staging of dread. Immigrants, globalists, leftists. These are the toxins that must be expelled from the body politic, the billowing clouds polluting the nation. And so the inward work that anxiety demands is left undone.

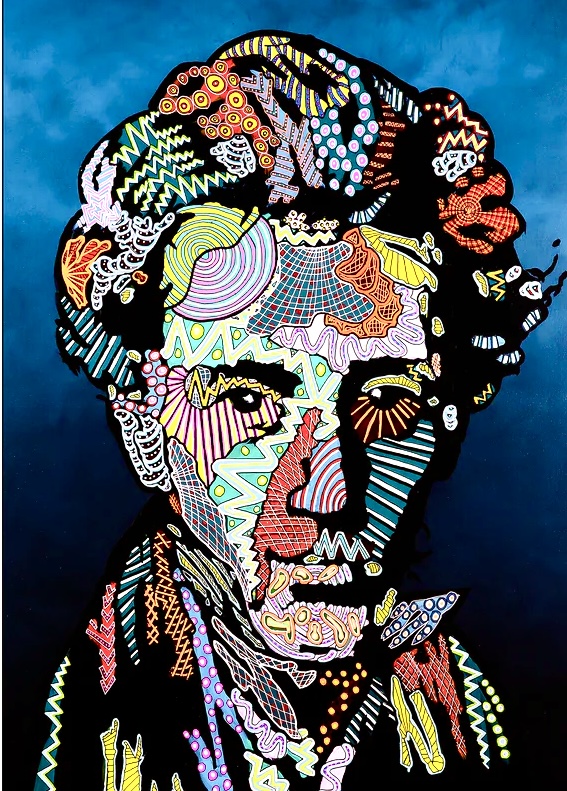

Nearly two centuries ago, a melancholy Dane named Søren Kierkegaard pondered the question of what it means to be anxious. Born in 1813 and dead by the age of forty-two, Kierkegaard wrote with the ferocity of a man racing against time.

“The ‘question of existence’ both animated and troubled him,” Clare Carlisle writes in her splendid Philosopher of the Heart: The Restless Life of Søren Kierkegaard. “How to be a human being in the world?” He wanted to know what it means to be anxious in the right way.

Kierkegaard’s great adversary was the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose vast system sought to reconcile every contradiction—between reason and faith, history and spirit. “Hegel’s system,” he said, “is like building a palace and forgetting to live in it.” It was a flight from the vicissitudes of life into abstraction unsullied by ordinariness.

You might say Hegel was Kierkegaard’s Trump. But instead of skyscrapers and golf courses, Hegel built a philosophical edifice. He welded history, logic, and spirit into a grand design—proof that one can build a massive structure entirely out of ego. Kierkegaard found it impressive, grotesque, and suffocating.

What would it mean to take up Kierkegaard in the present age?

A fiercely devout Christian who did not go to church, his thought does not lend itself to tidy prescriptions for a well-ordered life. Kierkegaard is a daring and elusive thinker whose writings form a tangle of paradoxes. To follow the rhythm of his mind is to feel the torques and schisms of existence itself. There is nothing easy or sentimental in Kierkegaard’s concept of dread.

Were he alive today, he would affirm anxiety’s biochemical factors and the real suffering that attends its chronic forms. I have written elsewhere – most fully in Evangelical Anxiety: A Memoir (HarperOne, 2022) – about the value of psychiatry, medication, and therapy, including psychoanalysis.

My concern here, however, is with Kierkegaard’s reflections on existential dread – the paradoxical discovery of the infinite possibilities of freedom within the inescapable constraints of finitude. And from this vantage, we can identify a few hard-won admonitions for our unsettled times—admonitions that begin, inevitably, with the unease we too often spend our days trying to direct elsewhere.

Receive anxiety as an opportunity. “That anxiety makes its appearance is the pivot upon which everything turns,” he wrote. Anxiety is ‘freedom’s possibility”. Its disruptions illumine the path to life lived freely, truthfully, and responsibly. Kierkegaard called this the work of “becoming the single individual”. What unsettles us is never merely a symptom but an invitation.

Accept anxiety as an awakening. Refusing the false comfort of “the crowd,” anxiety, borne rightly, enables the inner labor that refines perception. “A human being must be able to be truthful toward himself before God”, Kierkegaard said.

Acknowledge anxiety’s capacity to instruct. Kierkegaard speaks of being educated by anxiety as an apprenticeship with truth—an opening, an exposure to our ownmost fragility. “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom”: it strips away every false security and brings us face to face with the desperate, idolatrous ways we deny our selfish desires.

“The banality of evil,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “is the refusal to think.”

Kierkegaard knew, a century earlier, that authoritarianism begins with this demurral on responsibility and freedom.

During the years I lived in Berlin, I would sometimes step off the U-Bahn at Potsdamer Platz and walk to the German Resistance Memorial Center on Stauffenbergstraße. In the stone courtyard there you will see a statue of a solitary figure – naked, restrained yet unbowed – Richard Scheibe’s Der Widerstand, a tribute to the moral courage of those who defied the Nazi regime.

Against the Reich’s demand that the self be surrendered to the will of the führer, “the Resistance” honors the integrity of conscience and the self-respect that safeguards it. There is no action more noble than to stand on the bare ground of existence, stripped of illusion, resolved to be uniquely oneself. It is a memorial to the strenuous work of learning to be anxious in the right way.