I should start with a disclaimer: very few of the names from here on out will be real. Yes, Heather Warren and Nathan Walton are real people. I haven’t been lying retroactively or anything. But those names are easily found on the internet without my help anyway. This post, then, begins my pseudonyms.

I understand that lots of writers try to facilitate some kind of etymological connection between their characters and the real people from which they stem. Catullus, for instance, when he wrote about Clodia, calls her Lesbia. Not only are they metrically identical, but Lesbia refers to the Island of Lesbos where the Greek poetess Sapho lived and wrote. And in an early poem Catullus refers to Clodia as “Sapho’s Muse” (35). And so the thought is, if you are smart enough, you can make the connection from Clodia-> Sapho’s muse-> Sapho was from Lesbos-> Lesbia is Clodia. This will not be true of my pseudonyms.

Mine are meant to be merely symbolic, to match some facet of the name’s history to the real figure. So when I call a staff person Virgil, it’s not because his name has two syllables. It’s because, just like Virgil is the character that guides Dante through the Inferno, Lt. Virgil oriented us to the Albemarle Charlottesville Regional Jail.

Last week in the basement of the Albemarle Charlottesville Regional Jail (hereafter referred to as ACRJ) I underwent the mandatory orientation for every volunteer. Our session was particularly small because there was a tornado warning over Charlottesville—more accurately, there was a tornado over Charlottesville. “We usually have 20-40 people in these training nights,” Lieutenant Virgil began. “But a few people canceled because of the weather. So we’re gonna have more intimate evening.” There were five of us, including Nathan and me.

Virgil is a key swinging, story spinning, Mountain Dew wielding veteran of ACRJ. He started working at the jail 19 years ago—two months before I was born—and he, by his own admission, has seen it all. Every lesson comes with a tale. “Remember, a paper clip is deadly here. Few years ago, one of them left a paper clip in his own feces—I’m not tryin’ to be gross—left it in a cup and then stabbed a brother. No one caught it, died of infection.” He’s full of stories about gang fights, illicit convict-security romances and Big Bubba.

Big Bubba is Virgil’s anti-hero, a fictional character who represents the real power in the jail. “They’re not all bad guys. These inmates, they’ve probably got no problem with you. But, you never know what Big Bubba’s gonna make them do. This is Big Bubba’s house. Cause if Big Bubba says ‘give me your lunch’ what else are you gonna do? You just never know.” Right down to its central character, the jail is storied.

But these are cautionary tales, like my Italian mother used to tell. “One of my cousins tripped in her kitchen and the knives were facing up in the dishwasher…” “In school, girls could get reputations…” Somehow, with his stories and his veterancy, Virgil strikes me as maternal. I guess in a strange place, with dangerous people, you naturally look for someone to latch on to, to teach you how to live here.

“I like to start off with a short introduction and then two videos I like to show and then we’ll talk a little bit and, uh, that’ll do it. With this small a number though it shouldn’t take all that long.” Virgil put in a VHS and stepped back from the TV.

Here are a few of the notes I took.

“Security isn’t just a concern for security staff. It’s a concern for everyone.” I guess this is the point of this whole night.

“Don’t trust an inmate with any information about yourself.” Then how am I supposed to teach an autobiography class?!

“We should stop using the word trustee in the prisons. Not one of them is trustworthy, not even a trustee.”

“Do not share anything with an inmate.”

“At any time, if they wanted to, they could take this place over.”

Halfway through the first VHS, the tornado knocked out the power. All the lights died and a siren like a thousand cacophonous chalkboards filled the flashing room.

After twenty minute’s preaching how there was not single trustworthy inmate in the entire facility, I was trapped in their powerless house, like that scene from Dark Night Rises. I was half-prepared to see Bane come barreling through the barred door and rally a prison army. What is keeping this untrustworthy army from staging a coup d’état? I will not die in a jail uprising during a tornado. Where’s Batman? “Let’s just take it outside,” Virgil calmly yelled over the sirens. He led us out a side door, into the inferno, into the tornado. We huddled under a small awning to keep out of the pouring rain. Out of the jail and into the storm.

You see, I have been trained.

Not in self-defense or in classroom control, but in a storied kind of fear. When I tell people that I’m volunteering at the jail, the look on their faces say, Eh, it’s not a prison. The stories come in handy there. “But one time this guy got stabbed with a feces-covered paper clip…” I say it like it’s nothing out of the ordinary.

But my mind runs an endless parade of Office-Depot homicide scenarios. This is really what our training taught me to do: fear creatively. There was no hand-to-hand combat or issuing of badges and guns. There was no active self-defense. Just figure out how your clothing, your utensils, parts of your own body, can be weaponized before someone else does. You are a walking armament, self-destructive. Entering the jail, you have to strip down: glasses, pen, wallet, loose quarters all go in cubby 38. I usually feel naked just without my iPhone. This is like losing my skin.

Inside, it’s a scramble for fig leaves. My demeanor waffles between cold and polite—whichever, at the moment, seems the most effective form of protection. With every passerby—guard, prisoner, volunteer—there is a second of paralysis in which I re-arm myself. In the house, you are your only protection: expression, stance, stature. I have to hide behind myself. And I am not much to hide behind.

So many Christians think that at the heart of our religion is a binary: faith/doubt. So much has been written to explain and thus reinforce that binary. The prosperity Gospel, theological commiserations over the inability to believe, Dostoevsky. But it seems to me, from the New Testament at least, that the binary is actually one of faith and fear. Trust and fear. That seems a little bit more reasonable to me, a little bit more relatable. The question of trust and fear is not really one of knowing facts. It’s a way of standing before something we do not entirely understand–like God, or the World, for that matter. Bonhoeffer wrote of fear, “Nothing can make a human being so conscious of the reality of powers opposed to God in our lives.” Fear is a disposition, an orientation.

But then Bonhoeffer creates this call and response. “Fear is in the boat–Christ is in the boat.” Fear enters the boat, and Christ comes walking across the water. Fear enters the church, and the Spirit of God rests among them. Fear enters the prison; so do I. I have to bring Christ there. What does that mean? At first thought, I think it means to challenge the mechanisms of fear, to dwell on them and find their defeat. Christ is bigger than the system, bigger than the warden, bigger even than Big Bubba. He is bigger and he is near. Christ is in the jail. We are there to visit him. “Fear not. I am.”

Peter Hartwig is blogging this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Peter and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.

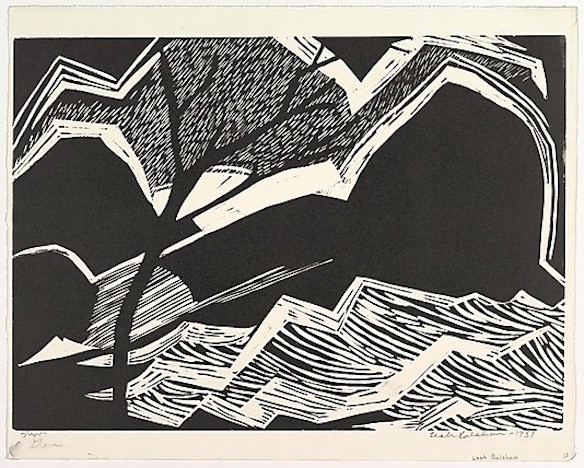

Image information: