by Emily Miller, 2022 Undergraduate Summer Research Fellow in Lived Theology

In order to set the stage for the many interweaving threads that form the contemporary complexities of First Baptist churches on Main Street and Park Street, let’s begin at a point in history that now only exists on paper: the original Charlottesville Baptist Church. In establishing some framing first, we can set the stage to dive deeper into the specific people and events that bring life and meaning to the congregations today.

1820 marks the first records of Baptist services taking place in Charlottesville, led by Reverend Daniel Davis at the Charlottesville Courthouse. Finally formally established in 1831, the Charlottesville First Baptist Church was located at the corner of Fourth and East Jefferson Streets. The original Charlottesville Baptist Church was home to many prominent Baptist Virginians, including Dr. John A. Broadus, former president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary; the two founders of the first college YMCA; and legendary Baptist missionary Lottie Moon, whom I will cover in more depth in a later blog post.

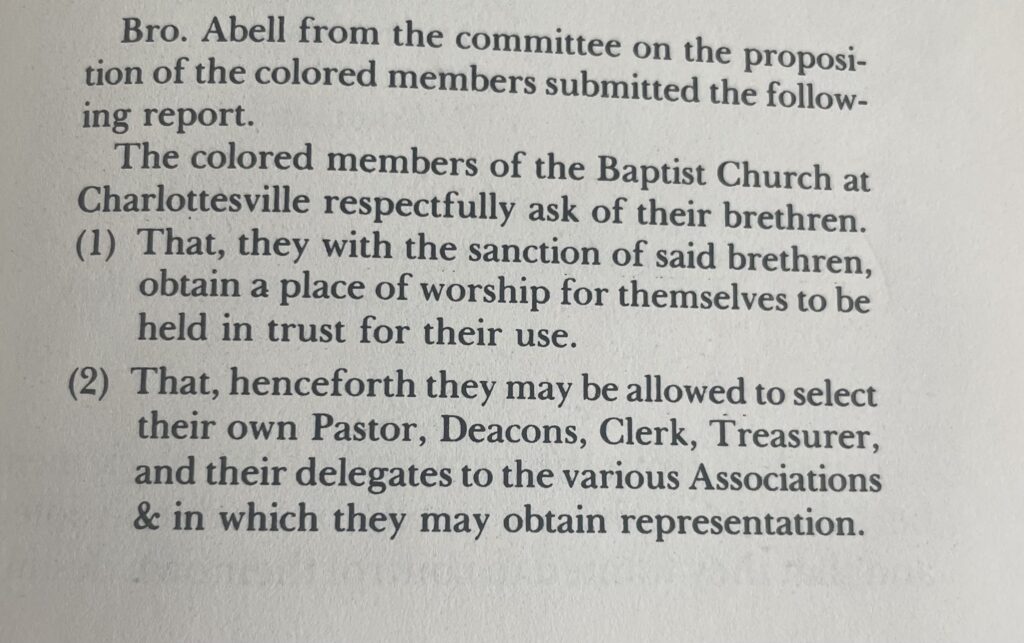

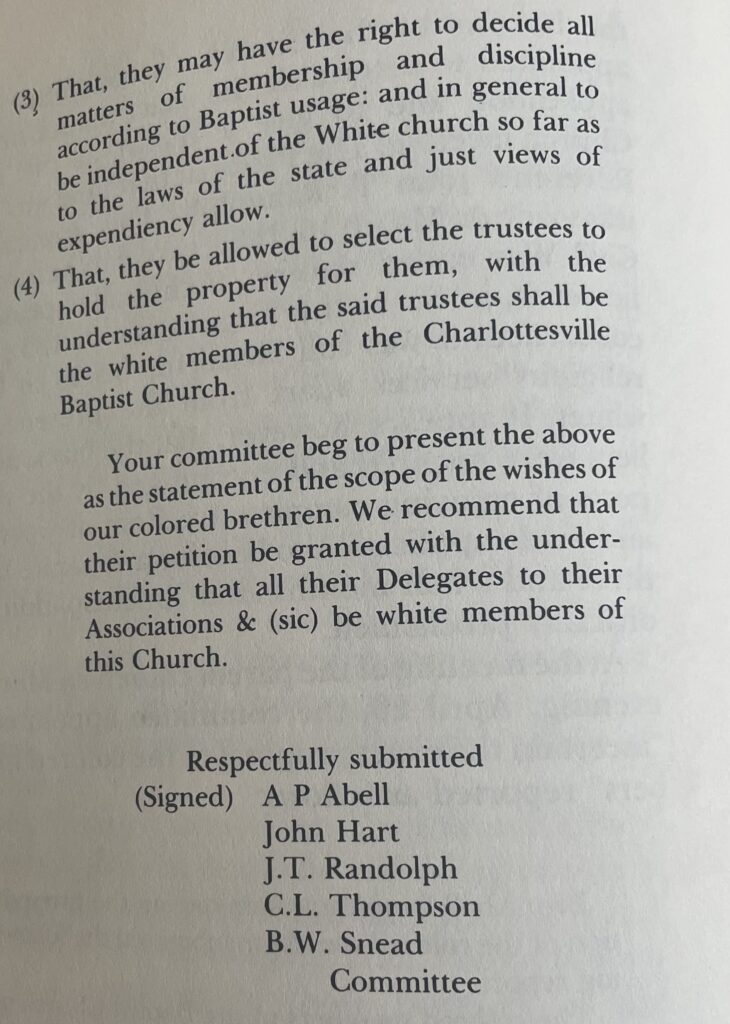

By 1863, at the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Charlottesville Baptist had approximately 800 black members, who by some accounts outnumbered the white congregants, despite the fact that black members were segregated to the balcony of the church. On April 20th, 1863, just four months after Lincoln’s issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the black members of the church issued an application through white church member C.L. Thompson to leave the church and form their own congregation elsewhere. I had the opportunity to sit down with Pat Edwards, historian at First Baptist Church on Main Street, who gave three main reasons for the split: the anxiousness of the black members of the congregation to become educated, their eagerness to take hold of church leadership that they had always been denied, and the realization that Emancipation could mean true freedom in more ways than one. The letter given to the governing board of Charlottesville Baptist by Thompson is below.

However, the break was not exactly clean. The formation of an independent church by black members with the conditions they set forth was a contested matter until over a year later in July of 1864 (in the meantime, the black members of the congregation met in the basement of Charlottesville Baptist). In fact, the black members made some concessions; namely, that the new black church had to have a white pastor—a Virginia law passed in 1832 made it illegal for African Americans to worship without a white minister present. The first three pastors at First Baptist Church on Main Street—Reverend J. Randolph, Reverend H. Fife, and Reverend J. George— were all white men. Reverend William Gibbons, who was formerly enslaved at UVA and in other parts of Albemarle county, became the first black preacher at First Baptist Main in 1868.

In the meantime, the two First Baptists experienced several location changes. Black congregation members had already been meeting separately in the parent church as well as the old Delavan Hotel, also called the “Mudwall” Building, located on West Main street. In 1868, the members of the new black church bought Mudwall, and in 1883 the new church building was completed as it is on Main Street today. As for First Baptist Church on Park Street, the building moved in October 1853 from Fourth and Jefferson streets to Second and Jefferson streets. On February 2nd, 1977, after plans for a new building had already been made, a fire destroyed the church and the current building was later erected on Park Street. It’s worth noting as well that Mt. Zion First African Baptist Church, now located on Lankford Avenue, is an offshoot of First Baptist on Main that separated during the nineteenth century, and that Jefferson Park Baptist Church, now located on Jefferson Park Avenue, is a church plant of First Baptist on Park (both offshoots will be covered in later posts).

Reading the bare-bones history of it all, I imagine more questions than answers come up in the minds of the reader (they would for me, at least). Who, truly, are the people behind these religious movements? How does this story intertwine with Civil Rights, integration, Charlottesville? As we go deeper and deeper each week, the picture will become clearer. Next week, I’ll introduce the Cabbell Family of UVA fame, and the ways that their influence shaped the history of UVA, Charlottesville, and most importantly, First Baptist Church.

Learn more about the Emily’s Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship in Lived Theology here.

The Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia is a research initiative, whose mission is to study the social consequences of theological ideas for the sake of a more just and compassionate world.