By Charles Marsh | February 10, 2023

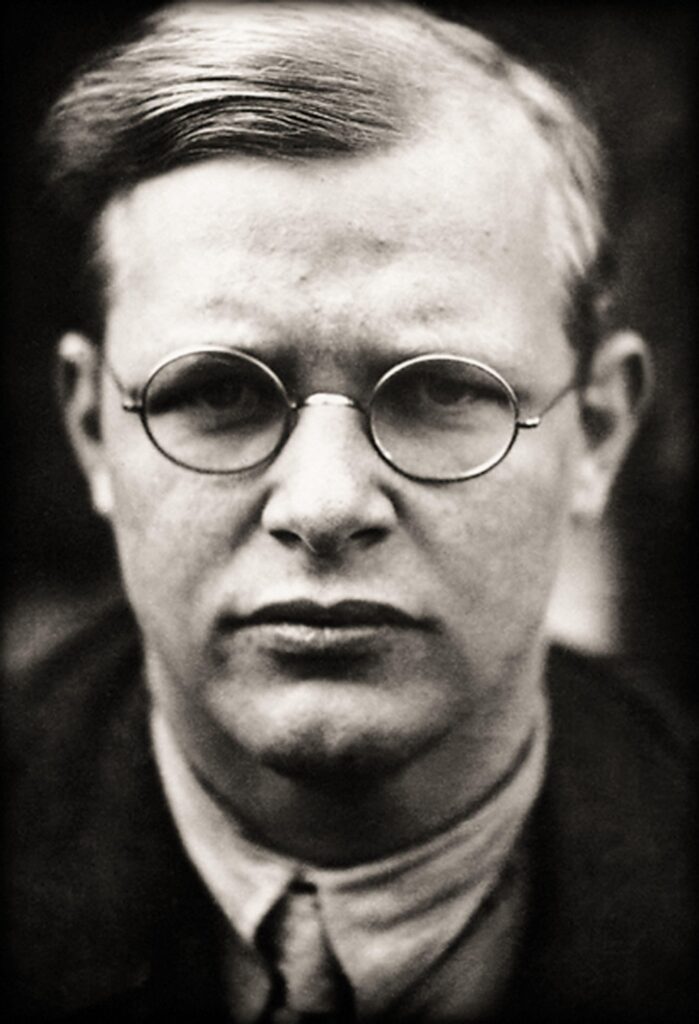

Born into privilege in a family of scientifically minded humanists, a 14-year-old Dietrich Bonhoeffer surprised everyone when he announced his decision to become a theologian. Less surprising was Dietrich’s response when an older brother asked, if I may paraphrase, “Are you kidding me?” “Look at the church,” the brother, in fact, said. “What a sad, paltry institution– and you hardly ever go yourself.” And Dietrich replied. “Then, in that case, I shall reform it.” Bonhoeffer is rarely observed in want of self-confidence.

Early on, Bonhoeffer had placed his hopes in the power of a prophetic Christian remnant to speak against the day and to inspire political dissent. In response to the new policies excluding Jews from church service, he issued a swift denunciation. A community that confesses Christ as Lord, he said, will do more than offer thoughts and prayers to those who wounded or crushed beneath the monstrous Nazi convoy; it will seek to break the wheels themselves. The church—which is to say, the global, ecumenical Body of Christ—stands before God, always and everywhere, with an “unconditional obligation” to the victims of society, regardless of whether the victims are Christians or non-Christians. Bonhoeffer spoke of Hitler as the Anti-Christ.

Bonhoeffer lived in a manner true to his essential convictions: taking each day as if it were the last, not in a spirit of fatalism or resignation, but wholeheartedly immersing himself in the present, borrowing hope from friends and family, relishing pleasures great and small, nourished by the Lord’s bounty, in expectation of a great future. “To think and to act with an eye on the coming generation,” he resolved, “and to be ready to move on without fear and worry.”

On January 30, 1933–twelve years after his vocational announcement—Bonhoeffer lectured at Berlin University on the Book of Genesis and the story of Cain, second son of Adam and Eve, who murders his brother Abel out of jealousy, and becomes the first “destroyer of life.” That same day, Hitler was appointed by President Paul von Hindenburg as the new Reich chancellor. Nothing would ever be the same—neither the world of the mind nor the world of politics, not Europe or the world outside it.

What happened to the landscape of German Christianity after Hitler’s appointment? The so-called German Christians continued to baptize and celebrate the Lord’s Supper and preach and run the country’s churches and theological schools (indeed, the universities full stop), all the while pledging their loyalty to the fatherland and to a fully assimilated Volkskirche, which is say, an ethno-national church based on common blood. The German Christians would give the doctrine of the Holy Spirit their best nationalist spin – casting the spirit as an ethos instead of a person of the Triune God: as “a nature spirit, a folk spirit, Germanness in its essence.” No less heretically, the German Christians would not confess that Spirit proceed from the Führer and the Father, and thus, from nature, history, and nation. God had chosen a new Israel, the German people, abrogating Israel’s ancient covenant – so declared the German Christians in what came to known as the disinheritance theory. Baptisms would be recast so as to include the prayer that “this child will grow up to be like the Fuhrer Adolf Hitler and Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler”. Research centers such as the Institute for the Study of the Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life – this one based in Wartburg Castle, where Martin Luther had translated the New Testament – recruited Germany’s best Biblical scholars, historians and theologians. Their mission was to systemically de-Judaizie the Christian faith[1], or as the founders explained, “to overcome everything based on Jewish influence in the ecclesiastical life of the German People, and to open the way for a faith, defined by the unfalsified message of Christ, to perform its service to the German People in the formation of its religious community.”[2]

To some degree, of course, the idea that framed the German Christian heresy originated in traditional Lutheran doctrine of the two kingdoms: Christians must be obedient to the earthly authorities as unto God. But the German Christians took a doctrine that had historically yielded a variety of views on church-state matters into an absolutist principle with catastrophic results: “Submit to Hitler with a joyful heart, in gratitude, as pleasing to the Lord,” read the new catechism. Make a “personal commitment to the Führer under the solemn summons of God”. Forge an “intimate solidarity with the Third Reich” and with the saintly man who both “created that community and embodies it.[3] United around Aryan ideals of masculinity and race, the German Christians would even try to convince themselves that Jesus had not been a Jew. The lesson here, of course, is that no one purporting to be a Christian can create an organic bond between God and nationhood without heretical consequences. From the time of Hitler’s ascent to power, Bonhoeffer devoted enormous energies to the preservation of the Gospel from the heretical assaults of Nazis who claimed to represent the Christian faith.

But Bonhoeffer would never reform the church. He would not even be able to inspire the Christian dissidents who formed the so-called Confessing Church to commit to a clear and concrete judgment against Hitler.

To be sure, the Confessing Church (bekennende Kirche) had rallied around a robust doctrinal orthodoxy and courageously protested the state’s intrusions into church affairs. The Confessing Church had formed in 1934 when delegates from the twenty-six regional churches of the German Evangelical Church met in the town of Barmen and signed a declaration opposing the majority’s embrace of Hitler.[4] The declaration, often anthologized in volumes of the great creeds of the church, is now known simply as the Barmen Declaration. Written by Karl Barth in a single all-night sitting, it is a forthright affirmation of the Lordship of Jesus Christ according to scripture and tradition: “ ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me.’ (John 14.6). But it is also an exercise in subversive indirection. Reflecting on John 14:6, for instance, the Declaration states, “Jesus Christ, as he is attested to us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death. We reject the false doctrine that the Church could and should recognize as a source of its proclamation, beyond and besides this one Word of God, any other events, powers, historic figures and truths as God’s revelation.”

The Barmen Declaration was bold as far as it went, denying the state’s pseudo-religious demands for complete obedience. If Jesus Christ is Lord over all worldly powers, the adoration of Hitler is idolatry. And indeed clergy and parishioners who supported Barmen would pay the price in arrests and imprisonment. But the Confessing Church never denounced the brutalities of the Hitler regime or take action against the state. It would never voice its support of the civil liberties of the Jewish people, nor denounce the Reich’s intent to create—in the words of historian Alon Confino—“a world without Jews.”[5]

The failure of the dissident church to mount a direct threat to Nazi power startled Bonhoeffer into a new way of thinking about the Christian’s witness in the world. His final writings refract the lessons of a chastened, in some ways, devastated faith. “We have been silent witnesses of evil deeds,” he writes. “We have become cunning and learned the arts of obfuscation and equivocation. Experience has rendered us mistrustful of human beings, and often we have failed to speak to them a true and open word. Unbearable conflicts have worn us down or even made us cynical.”

But it would not be enough to resist the Reich by appeals to its theological errors alone, important as such judgment are. It would be necessary to take concrete action. Bonhoeffer imagined the situation rather like this:If he were walking along the Kurfürstendamm in Berlin, or Oxford Street in London, and he saw some lunatic plowing his car into the crowd, he could not stand idly on the sidewalk. sidewalk. He would not say to himself, “I am a pastor. I’ll just wait to bury the dead afterward.” In whatever way he could, he would try to stop the lunatic driver.

Increasingly, in the years preceding his arrest on April 5, 1943, he found himself a voice crying in the wilderness, as he came to understand that moral responsibility obliged him to treason.

*

Before looking more closely at the historical collisions and theological breakthroughs that mark Bonhoeffer’s final two years, let’s begin with the question that inevitably arises in discussions of his legacy: why, and how, was he able “to see clearly, speak honestly, and to pay up personally” (to recall Albert Camus’s haunting words from his lecture, “The Unbeliever and the Christian”, given in 1948 at the Dominican Monastery of Latour-Maubourg) when so many others were not? All the qualities of an aristocratic heritage – courage in the face of danger, musical talent, intellectual curiosity, high-minded confidence and a cosmopolitan mind – coalesce in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s singular goodness.

Unlike other Protestant theologians of the twentieth century – Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, Rudolf Bultmann, the brothers Niebuhr, Herman Bavinck, Martin Luther King, Jr. – Bonhoeffer was not the son of a minister. Born on February 4, 1906, Bonhoeffer spent his first years in Breslau, with his seven siblings in a sprawling villa near the university clinics, where his father, Dr. Karl Bonhoeffer, taught and practiced psychiatry. In 1912, the year Dietrich turned six, his father was offered the chair of neurology and psychology at Friedrich-Wilhelms-University in Berlin, a prestigious post overseeing the clinic for nervous and psychiatric disorders, and the family moved into the leafy neighborhood of Grunewald, on the edge of a large urban forest by the same name.

Dietrich’s mother, Paula Bonhoeffer (nee von Hase), held liberal views on family and society–which is to say, encouraged the free, open, and orderly exchange of ideas–and presided over a domestic staff that included a governess for the older children, a nurse for the smaller ones, a housemaid, a parlor maid and a cook (and after the 1920s, a receptionist and a chauffeur). Paula Bonhoeffer observed religious rituals in the home, and all eight children were baptized; but she distrusted fanaticism of any sort and would not burden her children with spiritual demands. Dietrich was the exception among the four boys in showing an interest in theological matters. As a child, Bonhoeffer he to play a game with his twin sister Sabine that explored the idea of eternity. After they’d been tucked into bed and prayers were said, the two would lie awake trying to imagine this vast and mysterious notion. “Ewigkeit”, he might whisper. “Eternity”. Sabine found the word a little unsettling. Dietrich found it to be an “awesome word”.By the age of 21, Dietrich had written a doctoral dissertation titled Sanctorum Communio that would be hailed by the prominent Swiss theologian Karl Barth as a “theological miracle.” Three years later he successfully defended a second dissertation in Berlin with an exceedingly ambitious work called Act and Being; a treatise on how the Christian doctrine of revelation resolves certain philosophical questions about the nature of the self and the other – that also seeks to deconstruct the consequential Hegelian notion of an all-powerful human subject. It was an exercise requiring supreme self-confidence – which Bonhoeffer possessed in spades – that left him feeling at a loss. “Everything seems so infinitely banal and dull,” he wrote in a note.[6]

Ever a seeker of new ideas and easily bored, Bonhoeffer did the unexpected: he exchanged the comforts of the German professoriate for a peripatetic life. Between 1924 and 1932, he would to Italy, Spain, France, and Denmark, as well as to Libya, Morocco, Mexico, Cuba, and the United States. These travels included six weeks in Italy in the spring of 1924 – at the age of 18 – during which he reveled in the pageantry of Rome during Holy Week (not a typical rite of passage for German Lutherans) and felt “tempted” to convert to Catholicism, so enthralled had he become by its physicality and beauty – “magnifico!”, he wrote in his journal; a six month-immersion in African American Christianity primarily by way of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem – an experience that led to his remarkable claim at years end that he had heard the Gospel preached only in “the churches of the outcasts of America”.

Bonhoeffer reached Harlem through a fellowship exchange program at Union Theological Seminary in New York for the school year 1930 – 1931. Arriving in Manhattan late summer 1930, he was very much a rising academic star – with the two dissertations under his belt – and not inclined to think that Americans had a thing to teach him about theology. But when he left New York ten months later, he took with him a vital new understanding of his vocation as pastor and theologian.

Scholars have often noted that Bonhoeffer was underwhelmed by the liberal Protestant liberal thought he encountered in the 1930’s at Union Theological Seminary. “Is this a theological school or a training center for politicians?” Bonhoeffer is reported to have Reinhold Niebuhr after a lecture. The student were even worse; easily “intoxicated with liberal and humanistic phrases”, they talk a “blue streak,” but often without the “slightest substantive foundation.” But despite his grumblings over the lack of doctrinal rigor in American pragmatic theology (a fair criticism, and one the Union faculty might have received as a complement), Bonhoeffer was, finally, inspired by the example of the engaged theologian – by the applied theology of Niebuhr as well as numerous other professors and fellow students in this veritable laboratory of Christian social thought on the Upper West Side. It excited Bonhoeffer to think that the enterprise of theology pertained not only to doctrine, but to race, politics, literature, social justice, citizenship, and the complex realities of the day. The spirit of American public theology is present every time we hear Bonhoeffer say after 1931 that grace without ethical obedience is a betrayal of the cross; such grace is cheap.

In the tenement buildings of New York; in the literature of the Harlem Renaissance; in the worship, preaching, and song of the Black Church; and in the lived theologies that flourished in a city battered by the Great Depression, Bonhoeffer began to make what he would later term “the turning from the phraseological to the real”. After his year in America, Bonhoeffer would never again consider theology to be an activity confined to the academy, but part of the lived life in Christ.

In America, Bonhoeffer’s quest for a cloud of witnesses led him to a place where — to borrow from C. S. Lewis— he was “surprised by joy.” (C.S Lewis, who at 15 had pronounced himself “very angry at God for not existing,” became a Christian that same spring following a late-night walk with J. R. R. Tolkien.) When, in June of 1931, Bonhoeffer embarked on his return to Germany, it was with a new perspective on his vocation as theologian and pastor. Made alert to the joy of worshipping in the Black church and of grassroots ministry by the social gospel reformers, Bonhoeffer could now see his way to a more demanding and complex faith. Beyond any expectation, the year had set his “entire thinking on a track from which it has not yet deviated and never will,” he said.[7] “It was the problem of concreteness that concerns me now,” he said.

Back in Berlin in the fall of 1931, he began, for the first time, to nurture a rich devotional life, which was often animated by the African American spirituals and gospel standards. His daily readings followed the Moravian Prayer Book, which his governess had given him as a child. He organized spiritual retreats, sometimes held at his hut in the forest near Brenau, and he encouraged his students to read Scripture with openness to God’s voice and attention to the distressed and excluded. He taught his students African American spirituals and shared insights learned in the “church of the outcasts”. He was drawn into an intimate reading of the Sermon the Mount, the most inescapably demanding of the Gospel’s teachings, and at the same time he affirmed the Christianity essential bond with Judaism and with the Jewish people. Importantly, his understanding of the Lutheran doctrine of justification shifted in significant ways as well. He would no longer think of grace as a one-sided affirmation spoken by God to sinful humanity but a partnership between the divine and the human. The fundamental question was not how shall I be saved from the wrath of God, but what is the shape of a life lived “under the constraint of grace” and in obedience to Jesus.[8] The grace that frees is the grace that forms.

*

On Christmas Day, 1942, Bonhoeffer’s father read aloud a letter that Bonhoeffer had recently written to members of his family and to his associates involved in the conspiracy to overthrow Hitler. Much has been written about Bonhoeffer and the German conspiracy that adds to an already confusing story. Readers wanting a clear and thorough account of Bonhoeffer’s unique role would do well to find Sabine Dramm’s Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Resistance, listed in my recommendations for further reading at the end of this essay.

Suffice it to say, the German conspiracy was no uniformly coordinated national network, but a network of dissident cells that worked largely independent of the other. In the summer of 1939, Bonhoeffer had become a civilian member in the counterintelligence agency called the Abwehr, joining an elite group of conspirators that included Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Head of Military Intelligence, General Hans Oster, and Dohnanyi, in a plot to assassinate Hitler. Bonhoeffer’s role, however, would not get him near explosives or the actions of the July 20, 2022 coup attempt – as portrayed, for example, in the movie Valkerie.

Bonhoeffer’s brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi, had used his position at the Ministry of Justice to obtain confidential government records and compile a record of Nazi brutalities. The document, called “A Chronicle of Shame,” contained a day-by-day listing of war crimes, military plans, and genocidal actions and policies, the full realization of which made clear to Bonhoeffer that his principled commitment to Christian nonviolence must yield under these extreme circumstances to actions intended to “kill the madman”.

For ten years, Bonhoeffer had been on a collision course with Hitler. But what had been accomplished? Why had his efforts – and those of his fellow dissidents not only in the Kirchenkampf but in the wider resistance – failed to create any meaningful opposition or threat to the regime. What had gone wrong? Had they played too much music; sung Gregorian chants when they should have been crying out for the Jews; had they embarked upon an inner migration instead taking on the blood-stained face of history, worn their world-weariness as an exemption from moral responsibility?[9]

Though the letter of Christmas ’42 would come to be known by a name suggesting measured self-examination – “After Ten Years: A Reckoning Made at New Years 1943” – the title belies its anguished intent; to survey the ruins of the German nation and its apostate churches and to ponder the shape of Christian witness amid the brutalities of the present age. Reading “After Ten Years”, we meet Bonhoeffer in his last days of freedom and at the height of his intellectual powers.[10] Promising that the future will be uncertain and that personal goals will remain unfulfilled, everything in the essay – and let’s call it that, since there is no salutation, complimentary close or other elements of a letter – rushes toward the one inescapable question: “Are we still of any use?”

“After Ten Years” is Bonhoeffer’s rumination on the limits of religious dissent and the complexities of treason. The essay unfolds in a mannered, professorial, and at times diagnostic, fashion. It is indeed a reckoning with the high-minded principle that had distinguished such families as his own – an examination of those German who knew the importance of duty, whose moral imaginations had been shaped by the imperatives of Kantian reason, but who – Bonhoeffer concluded – “failed to reckon with the fact that duty, reason, and conscience could be misused in the service of evil.” In their book No Ordinary Men, the historian Fritz Stern and his wife, the writer, editor, and daughter of Reinhold Niebuhr, Elisabeth Sifton, called it “an unsparing assessment of Germans and their conduct over the previous decade” – though, I would add, the author himself is spared the harshest verdicts, and deservedly so.[11]

In earlier times, Bonhoeffer says, we might have expected the “reasonable ones” and the “ethical zealots” – the high-minded denizens of the Bildungsbürgertum – to meet evil with reason and principle; but despite their good intentions, or at least, the presumption of decency, they had, in this era of Fascism and violence, misread reality. Presuming that by the appeal to reason, morality, taste and an imagined superior discipline, they could protect a structure that was fast collapsing, they were crushed by colliding forces without accomplished a thing.

But the same qualities that had shaped these officious Kantian servants of the law, have now, in face of the “great masquerade of evil”, constrained free and imaginative action – precisely the kind of action that would otherwise enable civil courage. Withdrawing from conflict and confrontation “into the sanctuary of private virtuousness,” the good German chose the illusion of purity over the vexing insistence of injustice – resignation to defeat over a defiant venture of faith. Yet this was a false purity and an indulgent resignation. For in their deference to the imperatives of duty, they remained blind to the “one decisive and fundamental idea” that might have enabled vision and courage. Bonhoeffer speaks of “the need for the free, responsible action even against career and commission.” These last gentlemen and gentlewomen of the evening land– the presumed curators of virtue – fretting endlessly over the consequences of responsible action, in the end, closed their eyes to the injustice around them, remaining withdrawn and silent. “Disappointed that the world is so unreasonable, they see themselves condemned to unproductiveness; they withdraw in resignation or helplessly fall victim to the stronger.” In doing so, they forsake Jesus Christ.

“Who stands fast?”, Bonhoeffer asks.

“Only the one whose ultimate standard is not reason alone nor, principle, conscience, freedom, or virtue; but only the one who is prepared to sacrifice all of these in concrete response to God – the ones who answer the call to obedient and responsible action.[12]

*

When the knock on the front door, on the evening of April 4, 1943, three months after New Year’s reckoning, Bonhoeffer was sitting at his desk in his upstairs room. Some of his writings, including parts of his unfinished Ethics, were hidden in the rafters. The fictitious diary he had kept to disguise his conspiratorial exertions lay on his desk. He surrendered to Gestapo agents and was led out of the house in handcuffs. He was 37 years old and would remain in prison until his execution on the morning of April 9, 1945. Some popular biographers have trivialized Bonhoeffer’s prison writings, while some admirers theologians have read Bonhoeffer as if he had written nothing else. The Anglo-American Death of God theologians who had a fleeting fifteen minutes in the late 1960’s – and whose books you might still find in thrift shops and retiring faculty giveaways – represent the latter. Eric Metaxas is the most conspicuous of the occasional dilettante who wishes Bonhoeffer had written everything else except, he says, those “few bone fragments . . . set upon by famished kites and less noble birds, many of whose descendants gnaw them still” – by which Metaxas refers to the unflinching honest and searching theological writings that Bonhoeffer wrote on paper smuggled into and out of prison in the two years preceding his murder in a concentration camp.[13]

In fact, these luminous texts reveal new themes and directions that can only be understood in relation to the whole of Bonhoeffer’s thought.[14] Neither the death of God theologians nor Metaxas possess the interpretive discipline to understand the late works in their novelty and continuity.[15]

These writings, which would be posthumously collected and published in English under the title Letters and Papers from Prison, proceed as a montage of images, in lightning flashes of insight, written in metered and free verse poems, devotional meditations, Bible studies, reports on both prison life and the books he was reading, and theological fragments with breakthroughs both esoteric and thrilling. They remind us that so many of Bonhoeffer’s penetrating insights lie not in the answers he gave, but in the questions he asked. “Who is Christ for us today?”, “Are we still of any use?” “What is religionless Christianity?”, “Who am I?”

On the second Sunday of Advent 1943, Bonhoeffer wrote to his dearest friend Eberhard Bethge: “By the way, I notice more and more how much I am thinking and perceiving things in line with the Old Testament. In recent months I have been reading much more the Old than the New Testament.”

“Only when one knows that the name of God may not be uttered may one sometimes speak the name of Jesus Christ.”

“Only when one loves life and the earth so much that with it everything seems to be lost and at its end may one believe in the resurrection of the dead and a new world.”

Atheists who argue that Christianity is inherently world-indifferent would do well to read Bonhoeffer’s late works. Here Bonhoeffer ponders what it means to be Christian for the sake of the world. Many horrors have transpired in the course of human history because Christians turned their eyes upward and abandoned the narrow path for some imagined ladder of progress.

Surveying the German nation and its fateful allegiance to a brutal nationalist pigmentocracy, it was evident to Bonhoeffer that the “foundations are being pulled out from under all that is ‘Christianity.’” How has the Reformation church so utterly betrayed its theological inheritance—namely, that the sole basis of its existence is the Son of God born, crucified, buried, and resurrected for all humanity; that its speech and action are meant to bring glory to God, and to serve always and everywhere as sign posts towards that greater righteousness; that to be a follower of Jesus Christ means to be in the world according to a different standard than racial, national, or ideological orthodoxy?

And given those betrayals, how then should Christians live in this time after the age of religion? The question is the thematic thread that runs through Bonhoeffer’s final works. The answers scattered throughout the prison writings cover a kaleidoscope range of distinctive habits and discernments, and include keeping the language of the Gospel from profanation; learning to see history and to read Scripture with a “view from below”, from the perspective of the poor, the outsider, and the reviled; affirming out citizenship in the global, ecumenical church and ontological kinship with all who suffer for righteousness sake; confessing Christ as Lord over the powers and principalities; living in the present time for the sake of the coming generation, acknowledging earth’s distress; affirming the sacred character of all created life: confronting without apology our complicity in violence and exercising the humility appropriate to our fallible judgments; and speaking the Gospel, thoughtfully and with disciplined, so as to bring glory to God. These habits and discernment give shape to Bonhoeffer’s vision of Christian witness after the church’s fatal allegiance to Hitler.

In recent years, however, I’ve been thinking a lot about another theme in Bonhoeffer’s late theological repertoire, namely his idea of “a new nobility”. He only gives us a few hints about his imagings – with the promise always that he will return to the subject in a future letter.

Can one summon a new aristocracy when the old one has performed so badly. Bonhoeffer’s point is precisely to rethink the aristocratic ideal apart from class, family, or rank. He envisions instead a “new elite of people” who will form an aristocracy of responsibility—a nobility of righteous doers and prayerful pilgrims.

“It is exceedingly difficult to believe in God without a living example,” Bonhoeffer told Bethge. Protestants, and Lutherans in particular, he realizes, have historically not been inclined towards theologies of the Christian life enabled by human agency. But exemplification “has its origin in the humanity of Jesus,” Bonhoeffer says, “and is central in Paul’s writings). In these years after Christianity’s great profanation, when skepticism toward the faith increases among its cultured despisers, it will be necessary to show before we say.

And so there must be a return of the aristocrats of conscience. “Nobility arises from and exists by sacrifice, courage, and a clear sense of what one owes oneself and others, by the self-evident expectation of the respect one is due, and by an equally self-evident observance of the same respect for those above and those below. At issue all along the line is the rediscovery of experiences of quality that have been buried under so much rubble, of an order based on quality.” The order he envisions may first recall a bygone code of chivalry—by no coincidence, since that code arose with the ideal of the Christian warrior. But where the medieval knight saved the widow and the orphan from the infidel and the brute, in this day the danger was from the hollowing effects of totalitarianism and the leveling of all thought and feeling to the basest instincts. And to stupidity, which has now become calcified in the Nazi herd and the mass structures of the state. “Facts that contradict one’s prejudgment simply need not be believed.… —and when facts are irrefutable they are just pushed aside as inconsequential, as incidental.” Against such a corruption, only quality could mount an adequate defense, but quality must cease to identify itself with privilege and rediscover the imperative of honor; is must demand a return “from the radio to the book, from feverishly acquisitive activity to contemplative leisure and stillness, from frenzy to composure, from the sensational to the reflective . . . from snobbery to modesty.”[16] But even more, quality must renounce “the pursuit of position” and the cult of celebrity, in favor of “an opening upward and downward, particularly in the choice of one’s friends, a delight in private life, and the courage for public life.” Through prayer and righteous action, the aristocrats of conscience will safeguard “the besmirched words freedom, humanity, and toleration.”

Above all, though, the new nobility is marked by the excellences of Jesus Christ, spirited by a fierce love of the world, to take part “in Christ’s greatness of heart, in the responsible action that in freedom lays hold of the hour.”

How do we recognize these aristocrats of responsibility?

*

Some colleagues and friends found it odd that I followed my doctoral dissertation on Bonhoeffer with a book on religion and the civil rights movement. But the two are deeply allied in my mind – and more importantly, in their exemplification of redemptive Christian witness. The founding mothers and fathers of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States saw in southern and American exceptionalism “a dangerous tendency to turn the [region and] nation into an idol, and Christianity into a clan religion,” as the late historian Albert Raboteau wrote in his essential book, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South. The story of the Civil Rights Movement, 1955 – 1964, interpreted as a theological narrative, introduces us to a cast of characters who enact, embody and exemplify costly Christian witness in the American history. The movement that brought us the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the campaigns in Albany, Birmingham and Memphis, the Freedom Rides and Sit-Ins, the voter registration drives and the long, hot summers – this movement remained anchored in the energies, convictions, images of the Biblical narrative, in the disciplines of the Black church. The work of building beloved community clustered around the common grace of women and men, the privileged and the poor, who found themselves together, in the South, working in common cause towards a more just nation.

Among these people of exuberant faith, Fannie Lou Hamer, a former sharecropper in Ruleville, Mississippi, and a prophetic voice of poor African Americans in the Delta, gave voice to a lush and inviting faith, a fierce and disciplined love of Jesus Christ. Likewise, the simple, subversive act of Black students sitting down at a whites-only lunch counter, praying over their meals, praying for strength through the ordeals of hatred and violence, contained the seeds that would flower “into the greatest social witness of Christian nonviolence in American history”, as Thomas Merton wrote in his book Violence and Faith.[17]

These peculiar people exemplify a civil courage that “opens us and those around us to a force beyond ourselves, the force of righteous truth that is at the basis of human conscience.” Their patriotism is first and foremost for God’s Kingdom; their testimonies are difficult to hear. Mrs. Hamer was beaten and tortured in a Mississippi jail by white policies officers. “Doing good they are punished as evil-doers; being punished they rejoice, as if they were thereby quickened by life,” to recall the second-century letter that goes by the name, “St. Mathetes Epistle to Diognetus”, a remarkable inventory of the new habits and practices of this community gathering around the message of Jesus Christ. Who are these people?

American Christian institutions have spent vast resources seeking to raise up and nurture an army of elites to engage the culture wars. But Dietrich Bonhoeffer, this golden child of the Berlin Grunewald – which produced a generation of elites unparalleled in their erudition and aesthetics – directs us to “new sense of nobility being born that binds together a circle of human beings drawn from all existing social classes.” And in doing so, he directs us to an aristocracy that binds together the pastor murdered by a firing squad in a Nazi death camp and the lady who left the cotton fields to “work for Jesus” in civil rights and died in poverty.

“It’s a funny thing since I started working for Christ, “Mrs. Hamer said 1963 at a Freedom Vote Rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, some twenty years after Bonhoeffer’s reckoning. “It’s kind of like in the twenty-third Psalm, when he says, “Thou prepareth a table before me in the presence of my enemies. Thou anointed my head with oil and my cup runneth over.” And as a result I have walked through the shadows of death. But as long as you know you going for something, you put up a life.”[18]

On the day before his death, in the company of other prisoners of conscience, Bonhoeffer sang Bach’s cantata “Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”).

And though this world, with devils filled,

should threaten to undo us;

we will not fear, for God hath willed

His truth to triumph through us.

“Nothing is lost,” he wrote. “In Christ all things are taken up, preserved, albeit in transfigured form, transparent, clear, magnificent and consummately consoling.” From a higher satisfaction the below is revealed; the breadth and the height, heaven and earth, death and resurrection.

Bonhoeffer declares to us anew the hope that bears the sorrows of the world: “Again and again in these turbulent times, we lose sight of why life is really worth living. In truth, it is like this: If the earth was deemed worthy to bear the human being Jesus Christ, if a human being like Jesus lived, then our life as human beings has meaning.” The “Yes” and the “Amen” entered history, triumphed over the abyss. Be of good cheer. Spread hilaritas, he told a fellow prisoner. Learn to “be a disciple, clothed not in the adornments of nationhood and race, but having, as Paul tells the Galatians, ‘put on Christ.’” Live into the new humanity, join the new nobility. In this way, you can say, “Whoever I am, thou knowest, O God, I am thine.” In this way, you put up a life.

Further Reading

I recommend going deeper into Letters and Papers from Prison, then to his posthumously published Ethics, especially the section “The Church and the World”, and then on to Life Together, keeping in mind this Christian classic is not meant to be read as a manual on creating Christian community but as a poignant meditation on the gift of Christian fellowship. If you want to get a little off the beaten track, read Bonhoeffer’s journals from his first trip to Italy (he was 19 years old and enthralled by the color and pageantry of Holy Week in Rome), his sermons from London, where he served as pastor of two German-speaking congregations, his early speech to the ecumenical movement “Christ and Peace”; his journal entries from the summer of 1939, when he moved to New York City thinking he might sit out the war in the security of American academe, only to be overwhelmed by the conviction that he must return to Germany; and finally Bonhoeffer’s letter to his older brother, Karl-Friedrich, a brilliant scientist and an unbeliever, explaining his devotion to Jesus Christ and why he believed that “true inner clarity and honesty will come only by starting to take the Sermon on the Mount seriously.”

About Bonhoeffer

Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: A Biography. Translated by Victoria Barnett. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 2000.

Mary Bosanquet. The Life and Death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. New York: Harper and Row, 1968.

Sabine Dramm, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Resistance (Fortress Press, 2009).

Charles Marsh, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. New York: Knopf, 2014.

“Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Memories and Perspectives”, A Documentary Film, directed by Bain Boehlke, 1984.

On Christianity in the Third Reich

Bergen, Doris L. Twisted Cross: The German Christian Movement in the Third Reich. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

A condensed version of this essay recently appeared in a publication of the Trinity Forum Readings: Who Stands Fast, December, 2022)

Endnotes

[1] One of the founders of the Institute explained its mission: “The new truth of the moment is the völkische truth that every one must understand themselves as a member of a Volk, ‘an organic whole originating in race, bound to the land, and formed and impressed by its destiny’. ‘For this reason the opposition to Judaism is the very foundation of the recognition and realization of the völkische idea…for this reason, the battle against the Jews is the irrevocable obligation of the German People.” Cited in Peter M. Head, “The Nazi Quest for an Aryan Jesus” (JSHJ 2.1, 2004), p. 77.

[2] Cited in Peter M. Head, “The Nazi Quest for an Aryan Jesus” (JSHJ 2.1, 2004), p. 77.

[3]Cited in Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologian, Christian, Contemporary, pp. 504–5.

[4]The number 26 comes from Christiane Tietz’s Theologian of Resistance: The Life and Thought of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016), p. 48. The United States Holocaust Museum puts the number in its on-line Holocaust Encyclopedia at 28 regional churches.

[5] Alon Confino, A World Without Jews: The Nazi Imagination from Persecution to Genocide (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). At a church gathering in October 1938, Bonhoeffer asked his comrades in the church resistance whether “instead of talking of the same old questions again and again” (by which he meant the now effectively irrelevant issue of the church’s authority versus the state’s) it would not be better “to speak of that which truly is pressing on us: what the Confessing Church has to say to [this] question of church and synagogue?” He would now begin/began speaking of an equivalence before God of the church and the synagogue.

[6] Ibid., pp. 177–78.

[7] Bonhoeffer, DBW, vol. 16, pp. 367–68.

[8] Eberhard Bethge, Bonhoeffer, p. 182.

[9] Bonhoeffer, DBW, vol. 8, p. 52

[10] See Victoria Barnett, “Reading Bonhoeffer’s ‘After Ten Years’ in our Time”, After Ten Years: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and our Times (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017).

[11] Fritz Stern and Elisabeth Sifton, No Ordinary Men: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Hans von Dohnanyi, Resisters Against Church and State(New York: New York Review of Books, 2013), p. 100.

[12] Ibid., pp. 38-39

[13] “The simplest way to refute Metaxas’s dismissal of the prison theology,” the scholar Clifford Green wrote in a critical review, “is to note Bonhoeffer’s answer when Bethge asked him how the book he was writing on religionless Christianity related to the unfinished Ethics. Bonhoeffer answered that the book he was writing in prison was “in a certain sense a prologue to the larger work [Ethics] and, in part, anticipates it.” So, pace Metaxas, Ethics and the prison theology belong together.

[14] Bonhoeffer’s explorations of “the world come of age” and “religionless Christianity” – and of “living with and before God as if there were no God” – are explorations that go to the extremes precisely because of their anchor in the “redeeming and liberating love of Christ.” The flights of ponderous thoughts—and they are, to be sure, at times ponderous, Bonhoeffer’s saintliness notwithstanding–are like counterpoints that return time and again to their origin in the “clear and plain” cantus firmus of Jesus Christ.

[15] In an interview after his biography was published in 2010, Metaxas said, “[Bonhoeffer’s] legacy was hijacked by theological liberals, most notably the ‘God is Dead’ movement of the 1950s and 60’s, and it’s taken until now to begin to seriously set the record straight.” Five years later, Metaxas emerged as one of the most demonstrative evangelical supporters of Donald J. Trump, invoking Bonhoeffer as an ally to the dismay of anyone who’d ever read a book about German history. He has yet to set the record straight.

[16] Ibid, p. 48

[17] Thomas Merton, Violence and Faith (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968) p. 131.

[18] Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, “I Don’t Mind My Light Shining,” Speech Given at a Freedom Vote Rally, Greenwood, Mississippi, Fall/1963, To Tell It Like It Is: The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer, edited by Megan Parker Brooks and David W. Houck (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011), p. 5.