September 16, 2024

by Peter Slade

I have had a ringside seat as our culture war burned over Ashland, Ohio: a small college town that has long claimed to be the “World HQ of Nice People.” For 18 years, I have watched the town’s institutions–the Library and School Board, the City Council, the University, the Press, and churches– twist, turn, and some even break. I have spent my academic life studying Christians and churches in desperately divisive and morally demanding situations; now, I find myself in just such a situation. What, I have been wondering, does it mean to live faithfully and wisely in these times?

My most recent endeavor has been a public local history project.

Through a series of unusual events, in February 2024, I sat down with community members and staff from the Ashland County Historical Society to figure out a way to celebrate Juneteenth in our predominantly white and politically red town. We planned ice cream and cake and historical reenactors to explore the question, “What was the impact of the abolition of the institution of slavery here in Ashland?”

Researching Ashland County’s history from the 1840s through the 1860s, I encountered an extraordinarily polarized community. Businesses, law firms, churches, schools, colleges, and newspapers were all shaped by the arguments over slavery. Events reached a pitch in the summer of 1865 following Lincoln’s assassination. Barns burned, the papers reported death threats between Republicans and Democrats, and the town didn’t celebrate the 4th of July. When the troops “came marching home again,” Ashland found it difficult to “give them a mighty welcome then.” In July 1865, those organizing the “Grand Reception and Welcome” repeatedly postponed the parade and picnic as they tried to figure out how to exclude the county’s Democratic Party leaders (a crew with storm Copperhead allegiances). The Democrats in turn decried the event as “nothing but a JOHN BROWN, abolition fandango.”

The divisions in the town were particularly religious: noteworthy even by contemporary standards. When the preacher, professor, and future president Colonel James Garfield came to Ashland in November 1861 raising recruits for his regiment, he wrote to his wife;

“There is here a set of men who have not given up their partisan prejudices and are still more than half in sympathy with the South. Added to that there is a style of over-pious men and churches here, who are too godly to be humane.”

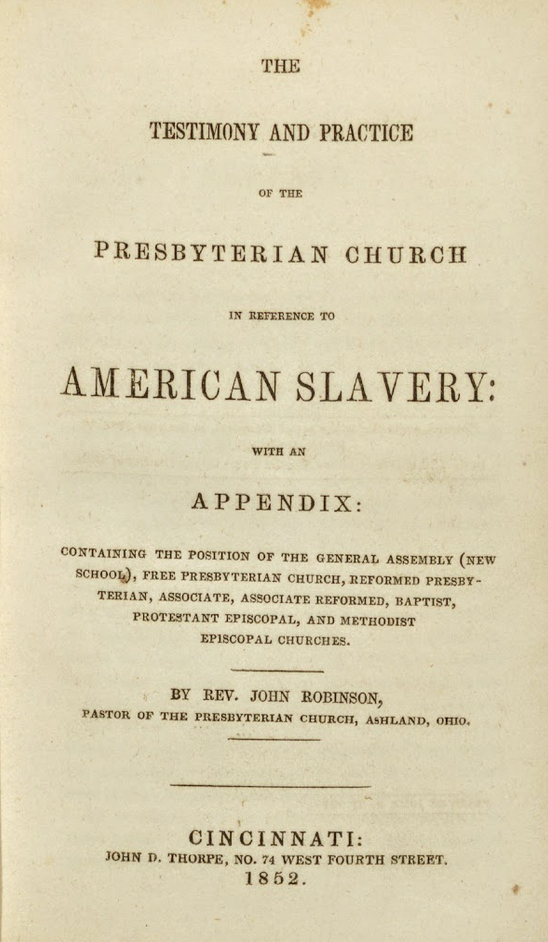

John Robinson, the pastor of First Presbyterian Church, published an apologetic in 1852–the same year that Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin— showing how Presbyterians could best work to end slavery without declaring slaveholding a sin. Robinson wanted to avoid a split in the Presbyterian Church which could contribute to secession. The most outspoken opponents of Lincoln and the War sat in Robinson’s pews.

In April, I joined the Rev. Hylden (the current occupant of Robinson’s pulpit) and some of the congregation of First Presbyterian Church, Ashland in reading through sections of Robinson’s book. From our current vantage point, we could understand his compromised position as a minister trying to hold a congregation together in such fractious and political times. He wanted to stay in the middle with “the moderate, wise, and good” and avoid the “antagonistic ultraisms” and “fanaticism” of the Abolitionists (the most outspoken of whom attended the Methodist Episcopal Church down the street). In the role of Rev. Robinson in 1880, Rev. Hylden, sweating in his black robe and wig, explained to the Juneteenth attendees:

I definitely didn’t call myself an Abolitionist. Back then, in the decade before the war, I thought Abolitionists were crazy fanatics who made it difficult for the reasonable people to come up with a peaceful compromise to end the evil system of slavery . . .

I am proud that my two oldest boys–John and William–fought to preserve the Union and played a part in bringing an end to slavery. Now, I believe the War was part of God’s Providential plan to end slavery and its passing from our land is not to be regretted–IT IS TO BE CELEBRATED

I hope there is something useful and instructive in understanding the theological, religious, and political forces playing out in a small Ohio town in the decades leading up to the Civil War. It has led my research further into this microhistory of my hometown. It is proving simultaneously a psychological escape from the current news cycle and a truly alarming window into “a style of over-pious men and churches. . . who are too godly to be humane.” My research has also introduced me to Seth Barber.

While serving as Ashland’s school superintendent and a teacher at the High School, Seth Barber answered Garfield’s evangelical abolitionist call to arms. As Captain Barber, he led a company of his former pupils to war. After losing a leg at Vicksburg, he returned to Ashland and his old job. There is no monument, marker, or plaque to this history. I suspect that, for political reasons, the town chose not to memorialize the Republican and Abolitionist Barber and his band of Ashland’s schoolboys.

I have spent days this summer at the Rutherford B. Hayes Archive reading Barber’s papers to learn more about this ignored character, hoping to learn more about his piety and humanity.

Seth Barber was an ardent young man. The son of a pioneer Methodist preacher from the Western Reserve, he heard a call to the pulpit: I found in his papers a license to preach issued in 1849 by the Liberty Baptist Church, Desoto County, Mississippi. He spent two years in Mississippi teaching and preaching while his fiance studied at Oberlin College, one of the principal centers of radical Abolitionism. It seems that Barber shared these beliefs. He wrote in 1851 that “the dark sin of slavery is cursing with heaven’s blackest curse the fairest portions of our country.”

He took the post of school superintendent in Ashland in 1852 and fought to maintain his professional credibility in a community determined to fracture along political lines. He made no abolitionist statements in his public writing, presumably in much the same manner as a school superintendent today would avoid pronouncements on abortion. Barber’s caution did not prevent “A Tax Payer” from writing to the paper in 1856 complaining that “our Superintendent . . . spends . . . his time lecturing on abolitionism.” It appears that school board meetings became a battleground. One former student wrote to Barber in 1860 warning of opposition:

It is [their] intention. . . [at] the next meeting for the election of members of the board to throng the place with a lot of Border Ruffians + elect a board of desperados. . . But I have too good an opinion of the people of Ashland to think that [they] could serve up enough of that class to fill the board although there may be more of them than we think.

Barber left Ashland in 1870 and died on his farm in Norwalk, Ohio in 1900. The carefully written obituary is poignant. There is no mention that he was ever a Baptist preacher; instead, it sketches a man of quiet personal piety.

“Believing the Bible, he showed his religion by the daily use of the Golden Rule. A simple prayer before meals was the only religious formula he was wont to utter.” (Norwalk Experiment, April 11, 1900.)

Seth Barber had found his answer to what it meant to live faithfully and wisely in his time.

Peter Slade is professor of the history of Christianity and Christian thought at Ashland University. He teaches and publishes in the area of American church history, race, and reconciliation. Read more on Professor Slade’s research.