Let us now praise a journal of radical theology and fine writing once published in a small Kentucky town.

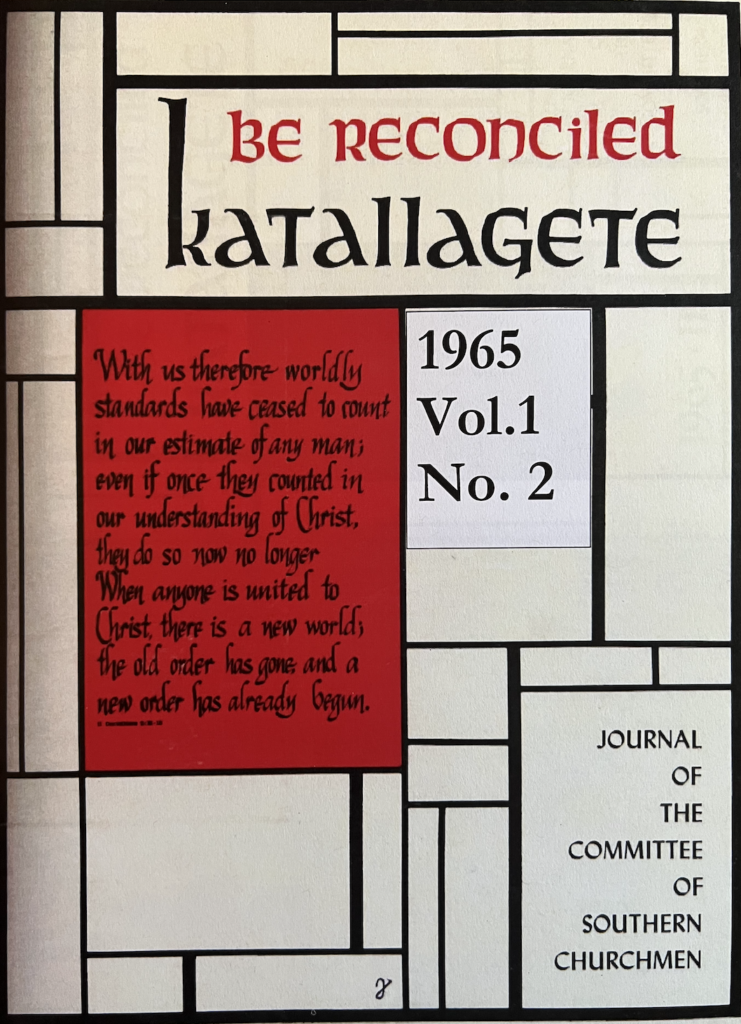

Katallagete — be reconciled! — is both the Greek word used by the Apostle Paul in his second letter to the Corinthians (“we pray you, be reconciled to God”), and the name of a journal, published a few times a year from a faculty office at Berea College, that espoused civil rights and Christian social activism during its publication run from 1964 until 1990.

Originally the magazine was a journal of the Committee of Southern Churchmen, but when the organization could no longer support it, Katallagete became independent. The contributors were a diverse group including author Walker Percy, Trappist monk Thomas Merton, activist Julius Lester, Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge, and French theologian Jacques Ellul. The magazine’s editor, James Y. Holloway, taught philosophy and religion at Berea College in Kentucky, and often collaborated closely with Will D. Campbell, the inside-agitator Baptist pastor perhaps best known for being fired in 1956 from his position as director of religious life at the University of Mississippi after speaking in support of racial equality – and for later befriending members of the Ku Klux Klan as a pastor and confessor. Katallagete’s politics were radical – and radical in a manner rarely associated with the American Left. It was influenced by Anabaptism and by the great theologians of the Social Gospel. Above all it was influenced by Karl Barth.

The journal’s “ungainly, emphatic title,” explains Jonathan McGregor in his brilliant new book, Communion of Radicals: The Literary Christian Left in Twentieth Century America, was just one of the ways the journals editors sought to “defamiliarize for southern readers the radical demands of a gospel to which they had become inured.”

Barth spoke of the priority of “God’s revolution” in movements and campaigns. This did not signal a turn away from concrete reality, but a reengagement with the concrete through a more pervasively theological framework. The journal was interested, finally, in the Kingdom of God; to its editor and contributors, the phrase denoted a reckoning that was political in the broadest sense, and that was never reducible to the tidy shibboleths that go under the name of social justice—for over and above all other movements is God’s movement, “cutting through all these movements as their hidden sense and motor.” The journal’s audacious theological goal, in other words, was to probe the creative origin of all particular movements that pursued human liberation and solidarity.

Over the course of its 36 year run, contributors to Katallagete addressed many contemporary issues from a Christian perspective—the war in Vietnam, income inequality, the status of African-Americans, the ordination of women, the Solidarity Movement in Poland, Death of God theology. As scholar Steven P. Miller has written, Holloway and Campbell saw themselves as offering a leftward critique of liberal politics and mainline Christianity. Many of the journal’s editors and contributors held degrees from Northeastern universities and seminaries, but the magazine was deeply and self-consciously Southern. It extolled the literature, music, rhythms and folk culture of the rural south, while lamenting the region’s abiding racism and violence. Kattelagete celebrated William Faulkner and the Grand Ole Opry; its covers often depicted sleeping hogs, church pulpits in the woods, labor union headquarters, and lush southern landscapes. In time, the journal reflected the growing awareness among dissidents and progressives, in and outside the South, that the Southern Way of Life had become the American Way of Life writ large.

To the extent that the periodical presents a single coherent vision, it called for an authentic, theologically robust, radically orthodox, populist southern Christianity that could also create deep solidarity between Blacks and whites. This, of course, was an ideal not realized; politically liberal evangelicals in 1976 backed Jimmy Carter’s Presidency and by the 1980s Southern white Christianity increasingly became tied with the political right. Despite the disappointment of the journal’s social hopes – a disappointment that its eschatology had always anticipated — the journal had a decisive impact on a generation of clergy, theologians and church-based activism. By 1974, over 9,000 people and institutions subscribed, an impressive number for a journal that often involved nuanced discussions of European theology and was printed with a mimeograph machine. Writing in Katallagete served to connect a geographically and denominationally separated group of intellectuals, as well as to provide a forum for up and coming voices like theologian Stanley Hauerwas.

Here’s a list of some of our favorite essays published in the journal:

William Stringfellow, “The Orthodoxy of Involvement”

Walker Percy, “The Failure and the Hope”

Thomas Merton, “Events and Pseudo-Events: Letter to a Southern Churchman”

Julius Lester, “Reflections on Reaching the Age of Thirty”

Fleming Rutledge, “In Search of an Authentic Biblical Feminism”

Jacques Ellul, “Lech Walesa and the Soul Force of Christianity”

Vine Deloria, Jr. “Non-violence in American Society”

Christopher Lasch, “The Cultural Civil War and the Crisis of Faith’

Daniel Berrigan, “Dear Friends in Christ” (A Eulogy for Civil Rights Martyr Jonathan Daniels).

Also worth noting: Hauerwas’s 1986 article, “How Christian Colleges are Contributing to the Corruption of Youth” (This article can be found in Hauerwas’ Christian Existence Today: Essays on Church, World and Living In Between).

We’re pleased to introduce the Katallagete story to a new generation and share with you some of its treasures, beginning with the nine articles listed above – we would love to hear your ideas and reactions. We are also including the complete Katallagete index here.

Charles Marsh (UVA/PLT) and Isaac May (Yale Law School) A special thanks to Dr. Nathan Walton, Co-Lead Pastor East End Fellowship (Richmond, Virginia), who served as the Graduate Research Fellow at the Project on Lived Theology from 2015-2018, and heroically brought our bankers boxes of Kattalagges to digital format.