The Women Who Influenced Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Leymah Gbowee and the Women’s Liberian Mass Action for Peace, and the Necessity of Just and Inclusive Processes post bellum

Meghan Topp Goodwin is a Graduate Research Fellow at the Project on Lived Theology and doctoral student in the religious studies department at the University of Virgina. She also serves as Associate Director of Government Relations for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). These research insights comes from a semester long tutorial with Dr. Guy Aiken, PLT postdoctoral fellow and guest lecturer in the religious studies department at UVA.

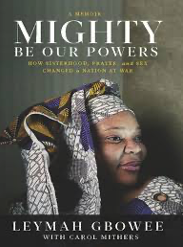

In her groundbreaking paper, “Women in Christian Peacebuilding Movements,” Meghan Topp Goodwin argues that women’s leadership not only was crucial to the success of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and to the movement to end the Second Liberian Civil War (1999-2003), but also is necessary for any lasting peace. Goodwin takes as her models the still-underappreciated Rosa Parks and the Nobel Peace Prize-winner Leymah Gbowee. Goodwin laments the sexism that prevented Parks from becoming the spokesperson for the Montgomery Bus Boycott and, by extension perhaps, for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement as a whole:

“[King] believed himself destined to change the course of U.S. history and change it he did. But I add, with the small and often-silenced voice of women in history, whether Rosa Parks might not also have been destined for a more prominent role, whether a more just arc of history might have included Rosa Parks, permitted to speak to [thousands of] people inspired by her leadership just before the leadership of the MIA [Montgomery Improvement Association] was chosen, freed from the oppressive subjugation of her sex at the same time that the nation rose up to break the oppressive shackles of segregation.”

Goodwin then celebrates the staggering resilience, resolve, and creativity with which 2011 Nobel Peace Prize-winner Leymah Gbowee turned that very sexism to her advantage in Liberia. Gbowee’s own pilgrimage to nonviolence began with the Bible:

“She describes, in her youth, running from her [husband and] abuser: ‘One night, I ran from the bedroom, my nightgown in pieces, grabbed my Bible and shut myself in the bath. “God,” I said, “Guide me with a verse.” I let the book fall open: Isaiah 54. “For the Lord has called thee as a woman forsaken and grieved in spirit….O thou afflicted, tossed with tempest, and not comforted, behold, I will lay thy stones with fair colors, and lay thy foundations with sapphires.”….I came back to Isaiah 54 again and again over the next decade. I knew it was my promise.”

Gbowee then led the Women’s Liberian Mass Action for Peace in using shame, sex strikes, and other nonviolent tactics to help force an end to the country’s second civil war:

“Like Gandhi and King before her, Gbowee saw complicity with injustice as a moral wrong, and action for justice a moral imperative. When violence broke out again in Monrovia while endless ‘peace talks’ at a U.N. Conference led to nothing, the women had had enough. Just before the conference’s lunch break, the women looped arms and blocked the doors. ‘No one will come out of this place until a peace agreement is signed,’ Gbowee said. When security guards approached her, she threatened to strip naked. ‘In threatening to strip,’ she explains, ‘I had summoned up a traditional power. In Africa, it’s a terrible curse to see an elderly or married woman deliberately bare herself….Fear passed through the hall. “Madame, no!” cried a general present.’….‘The Liberian war didn’t end of the July day we blocked the hall in Accra,’ Gbowee wrote, ‘but what we did marked the beginning of the end. The atmosphere at the peace talks changed from circuslike to somber. On August 11, Charles Taylor resigned the presidency and agreed to go into exile in Nigeria.’”

Finally, Goodwin turns to contemporary Catholic thinkers to show that women’s leadership in post bellum processes and institutions is necessary for lasting peace:

“Inclusion of women in peace processes is associated with more sustainable peace. ‘The evidence is overwhelming,’ found a report by Inclusive Security. ‘Where women’s inclusion is prioritized, peace is more likely—particularly when women influence decision-making.’ This is because women tend to moderate extremism, promote dialogue, bridge divides and mobilize coalitions, and prioritize different issues during peace processes than men would. Women suffer more severely in conflict, especially in ethnic wars and wars in failed states due to the indirect effects of war such as human rights abuses, economic devastation, infectious diseases, and a breakdown in social order. ‘Perhaps because of these unique experiences during war,’ writes Marie Reilly, ‘women raise different priorities during peace negotiations. They frequently expand the issues under consideration—taking talks beyond military action, power, and territory to consider social and humanitarian needs that belligerents fail to prioritize…[and to] address development and human rights issues related to the underlying causes of the conflict.”

Goodwin’s paper is available on our Resources page here.