By Guy Aiken, PLT Research Fellow

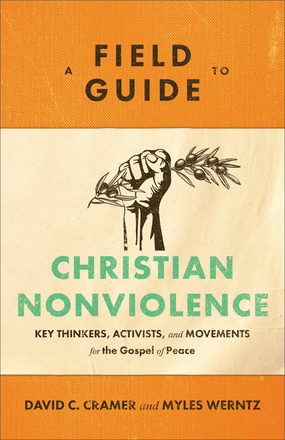

A Field Guide to Christian Nonviolence (Baker Academic, 2022) is an impressive—and impressively concise—book. David Cramer and Myles Werntz cover a lot of ground, all the while drilling down in well-chosen spots. Their book more than earns the praise (hardly a given in the publishing business) lavished on it by the likes of David Gushee, William Cavanagh, and Lisa Sowle Cahill in their back-cover blurbs. Gushee offers the most pragmatic recommendation, that the book “will be featured in all [his] peace and war classes at both the undergraduate and seminary levels for years to come.” He also inadvertently identifies my frustration with the book, which he predicts “will become the indispensable textbook that with relative simplicity introduces the varieties of pacifism to…Christian audiences” (emphasis mine). Are pacifism and nonviolence synonymous? Gushee is right that the book assumes so. But I don’t think they are. To treat them that way, I think, prevents a clear understanding of each.

But first, the excellence of this book, and why, if you’re studying or teaching a class on Christianity and violence, you should read it. Cramer and Werntz distinguish eight types or “streams” of Christian nonviolence: “nonviolence of Christian discipleship,” “nonviolence as Christian virtue,” “nonviolence of Christian mysticism,” “apocalyptic nonviolence,” “realist nonviolence,” “nonviolence as political practice,” “liberationist nonviolence,” and “Christian antiviolence.” Each type gets its own chapter. Cramer and Werntz define the type near the beginning of its respective chapter, explain how it differs from the other seven types (while acknowledging inevitable overlaps), and then flesh it out by providing thumbnail sketches of the ideas and practices of some of each type’s representative figures.

Let’s take the first chapter, on “nonviolence of Christian discipleship,” as an example—especially since it discusses Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder, a foundational figure on nonviolence for the two authors. Cramer and Werntz, along with the rest of the world not already in the know, learned about a decade ago that Yoder was sexually assaulting women even as he was popularizing “ecclesiocentric nonviolence,” which Cramer and Werntz characterize as “a way of living in the world, shaped by reading of the Scriptures, corporate worship, and the practices of life together” (the last phrase a nice nod to Bonhoeffer’s Life Together). What distinguishes this type from all the others is that it considers nonviolence constitutive of church: a violent church is an oxymoron. But Yoder himself was violent. If nonviolence can be reduced solely to that of Christian discipleship, with Yoder as its representative figure, then Christian nonviolence is “undermine(d)…on its own terms.” Refusing to let that happen, Cramer and Werntz not only identify other representative figures of this type of nonviolence—namely Nazi resistors Andre Trocme and Dietrich Bonhoeffer—but they also, of course, distinguish seven other types of nonviolence that cannot be reduced to Yoder and his The Politics of Jesus (1972).

Ingeniously, Cramer and Werntz arrange the book along the lines of Reinhold Niebuhr’s dichotomy between nonviolence as Christian witness (“inward-focused”) and nonviolence as an instrument of concrete worldly change (“outward-focused”). Cramer and Werntz’s first four chapters/types fall loosely into Niebuhr’s first category, the last four into the latter. Ironically, Cramer and Werntz don’t get Niebuhr himself quite right, at least not the Niebuhr of Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932). “Where nonviolent realists part from Niebuhr,” they claim in their chapter on Realist Nonviolence, “is over his insistence on the necessity of violence to establish…relative justice.” In Moral Man, Niebuhr insists on no such thing. “For nonviolent realists,” as opposed to Niebuhr, they continue, “nonviolent peacemaking initiatives are almost always more effective than war in establishing justice.” This is actually much closer to what Niebuhr argues in Moral Man. Cramer and Werntz appear to be reading Niebuhr’s endorsement of just war in the face of Hitler back into his earlier writings on nonviolence.

This leads me to my frustration with the book’s conflation of pacifism and nonviolence. I think a more accurate, if unwieldy, title for the book would have been A Field Guide to Non-Warlike Christian Responses to Violence. “Christian antiviolence,” for instance, according to Cramer and Werntz, is not exclusively nonviolent. Rather, it is resistance against gender and sexual violence, a resistance that could itself conceivably use violence against the perpetrators of gender and sexual violence. And representatives of the second half of the book—whom I would call nonviolent activists—have often looked to various sorts of police power to enforce more just social, economic, and political relations, while representatives of the first half of the book—whom I would call pacifists—have often seen police power itself as an instance of unchristian, or even satanic, violence.

Cramer and Werntz believe that such sharp disagreement is why we need the pluralist understanding of Christian nonviolence they provide with this book. But this pluralist understanding relies on a definition of nonviolence that the two most outstanding practitioners of nonviolence in the twentieth century, Gandhi and King, rejected and lamented as a woeful misunderstanding. “In its most common forms,” Cramer and Werntz assert in their chapter on “apocalyptic nonviolence,” “nonviolence pertains to the refusal to kill another human or to general opposition to war.” It’s this sort of negative definition of nonviolence that most students bring with them to the first class of my course on nonviolence in America. But it’s not how Gandhi and King understood nonviolence. Gandhi called nonviolence “a force which is more powerful than electricity” and “superior to all the forces put together.” King called it “a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love.” Not being violent is not the same as nonviolence. Nonviolence is a positive act of loving your opponent as yourself. And the way you do that in situations of conflict is by suffering violence rather than inflicting it, in the faith that your suffering will change the world.

Whatever my problems with Cramer and Werntz’s definition of nonviolence, it allowed them to write this fine book. Read it, and profit from it.

For more, watch Guy Aiken’s lecture “Kingdom Come: King and the Third Way of Nonviolence.”