This is the third in a series of blog posts with reports and reflections by Peter Slade on his two-week lived theology road trip from New Orleans to Memphis in September 2013.

I arrived at Redeemer Presbyterian Church at 9:30 in time for Sunday school. Redeemer is a young, vibrant, interracial church in Jackson, Mississippi. As I waited in a corridor for the first service to let out, I saw an older African American gentleman in a light brown suit sitting patiently. I realized that I was waiting for Sunday school with James Meredith, the man who integrated the University of Mississippi back in 1962. I told him how much I had enjoyed reading his recent book A Mission from God: A Memoir and Challenge for America.

“You read all of it?”

“Yes sir.”

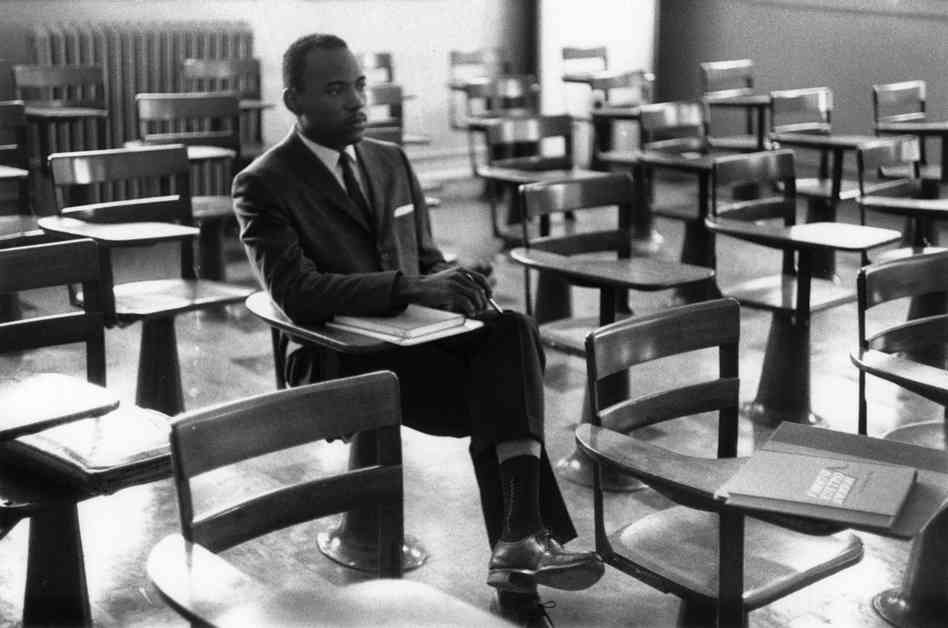

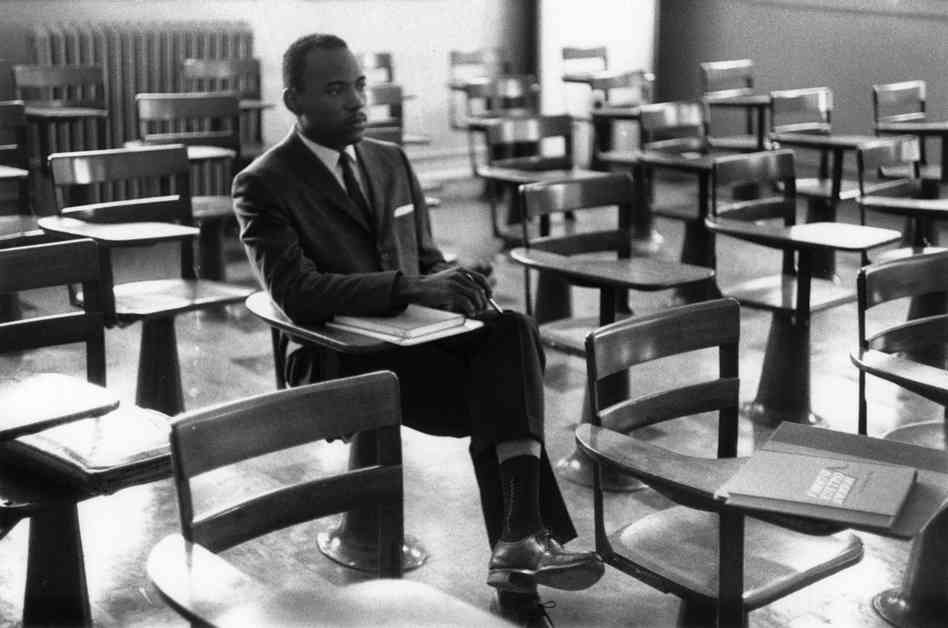

After introducing myself as a graduate of Ole Miss I asked him if I could go with him to his Sunday school class. We went into the classroom and sat in rows of folding metal chairs–whites and blacks–and we were lectured on Paul’s letter to the Galatians by an African American student from Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS). When Meredith went to his first classes at Ole Miss over 50 years ago, none of the white students would sit next to him, and when RTS opened its doors in Jackson in 1964, to combat the social and theological liberalism of the denomination’s seminaries, there were no black seminarians.

James Meredith on his first day of classes, University of Mississippi, 1962.

Sitting next to Meredith in that Sunday school room, I contemplated how much can change in one lifetime.

It turns out that this is my week for meeting Mississippians who have seen unimaginable social change in their lifetimes. On Tuesday I gave a lecture for the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) on the Legacy of John Perkins. This started as an invitation on a Facebook comment thread to come to an informal brown bag event at the MDAH building; by the time I got to Jackson, somehow this had become a lecture in the house chamber of the Old Capitol building with former governor of Mississippi, William Winter introducing me. Born in 1923, Winter’s grandfather was a Confederate veteran. The Civil War is only two lifetimes away.

The setting is intimidating: I am speaking in the chamber where Mississippi decided to secede from the Union, and John and Vera Mae Perkins are present to hear what I have to say. In his introduction, William Winter thanks Perkins. Referencing the Damascus road story (Acts 9), he says, “He caused the scales to fall from my eyes on the matter of race.”

(L. to R.) Peter Slade, John Perkins, Vera Mae Perkins, William Winter

My lecture traced Perkins’ life from a cotton plantation in Simpson County in 1930 through his 53 years as an apostle to the white evangelical church. In the lecture I suggested that this lifetime spent preaching reconciliation and economic justice in white pulpits has weakened the bond between a reactionary social conservatism and a inerrantist biblical hermeneutic. This means that in the twenty-first century many self-identifying “Bible believing Christians” can contemplate Perkins’s radical message of Relocation, Redistribution and Reconciliation without dismissing him as a heretic. This is a remarkable ideological shift from the 1950s and 1960s when evangelicals failed to support the Civil Rights Movement, dismissing its goals as “integration without regeneration.”

Thinking over this lifetime of change witnessed by Meredith, Winter, and Perkins, I realize that if you measure change in decades, the desegregation of hearts and minds is taking a long time. But if I shift my perspective to measuring change in lifetimes, then things look different.

How long does change take, and how long should we wait for change? These are familiar questions to historians of the Civil Rights Movement.

I am writing this blog post sitting on the balcony of Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, and my mind naturally strays to Oxford’s favorite literary son: William Faulkner. In the March 5, 1956 issue of Life magazine, there was a photo essay on the ongoing Montgomery bus boycott: “A Bold Boycott Goes On.” At the end of the article, readers were promised a commentary on this surprising turn of events. “For one celebrated Southerner’s personal views on how to check this rise [in ‘racial hostility’] turn to pages 51, 52.” The celebrated Southerner was Faulkner who wrote:

“I must go on record as opposing the forces outside the South which would use legal or police compulsion to eradicate that evil [of compulsory segregation] overnight . . . I would say to the NAACP and all organizations who would compel immediate and unconditional integration: ‘Go slow now. Stop now for a time, a moment.’”

Historians call this position gradualism. Gradualism was the idea put forward by white moderates in the 1950s and 1960s that change would come to the South if outside agitators would just leave well enough alone and allow southerners to take care of their own business. The leaders of the Montgomery Bus Boycott were unimpressed with Faulkner’s plea. On April 14,1956, in a speech to the NAACP in Columbus, Ohio, Martin Luther King took William Faulkner to task.

I am on the road and my googling skills are obviously not up to finding the text of that 1956 speech. However, in 1963, in his famous Letter from Birmingham City Jail–a response to white moderates–King shot back this blistering statement:

For years now I have heard the words “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” . . . We must come to see with the distinguished jurist of yesterday that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

It occurs to me that these white southern gradualists had the wrong prescription but the right prediction. (I checked with a Baptist preacher friend and she said this would preach!) Their prescription was wrong because there clearly needed to be people like James Meredith and John Perkins (both inside agitators) to challenge the system of white supremacy. However, their prediction that it would take southerners (black and white) a long time to overcome the crippling effects of slavery and Jim Crow was correct.

Sitting at the back of the house chamber listening to my lecture was Rev. Ed King. Now in his seventies, King was prominent in the movement in Jackson. Kelly Figueroa-Ray, the assistant director of the Project on Lived Theology, had driven up to Jackson with her daughter for the Old Capitol event, and after the lecture, we headed to the Mayflower on Capitol Street. After our late lunch we crossed the street to the location of the old Woolworth’s store. There is now an historic marker to remind passersby that this was the site of a famous sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter. Rev. Ed King had been present as his students from Tougaloo College were abused and attacked by a white mob. We stand there taking pictures in the heat.

Sitting at the back of the house chamber listening to my lecture was Rev. Ed King. Now in his seventies, King was prominent in the movement in Jackson. Kelly Figueroa-Ray, the assistant director of the Project on Lived Theology, had driven up to Jackson with her daughter for the Old Capitol event, and after the lecture, we headed to the Mayflower on Capitol Street. After our late lunch we crossed the street to the location of the old Woolworth’s store. There is now an historic marker to remind passersby that this was the site of a famous sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter. Rev. Ed King had been present as his students from Tougaloo College were abused and attacked by a white mob. We stand there taking pictures in the heat.

“You’ve lived to see Mississippi change,” I throw out there.

“We just did what we knew was right. We didn’t know if we were going to succeed. We just had to do something.”

Maegan Parker Brooks and Davis W. Houck have compiled a volume of twenty-one of Fannie Lou Hamer’s most important speeches spanning her civil rights career, entitled The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It Like It Is. Published by University Press of Mississippi, this is the first collection of her speeches ever published.

Maegan Parker Brooks and Davis W. Houck have compiled a volume of twenty-one of Fannie Lou Hamer’s most important speeches spanning her civil rights career, entitled The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It Like It Is. Published by University Press of Mississippi, this is the first collection of her speeches ever published.

On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

Sitting at the back of the house chamber listening to my lecture was

Sitting at the back of the house chamber listening to my lecture was