Although I’ve been working in the Tenderloin for ten weeks now, I recently spent the night there for the first time. Before settling in for a night of long conversations, junk food, and Netflix in their apartment, my fellow interns and I made the long trek (0.7 miles) to the Trader Joe’s in Nob Hill, just beyond the borders of the TL. “Heading up to Snob Hill,” one of the interns joked. I played along: “You know you’ve reached gentrification when you reach Trader Joe’s.” But even as I said this I had to admit, I have no idea what it’s like to live in an environment where gentrification is an active threat.

Although I’ve been working in the Tenderloin for ten weeks now, I recently spent the night there for the first time. Before settling in for a night of long conversations, junk food, and Netflix in their apartment, my fellow interns and I made the long trek (0.7 miles) to the Trader Joe’s in Nob Hill, just beyond the borders of the TL. “Heading up to Snob Hill,” one of the interns joked. I played along: “You know you’ve reached gentrification when you reach Trader Joe’s.” But even as I said this I had to admit, I have no idea what it’s like to live in an environment where gentrification is an active threat.

This summer I choose the more economic option to live with fellow PLT intern Melina Rapazzini and her family outside of the city rather than living in the city of San Francisco. Melina and her family are wonderful and a joy to live with, and this was the only way to make this opportunity financially possible, so I don’t regret the decision. However, part of my reflective process this summer has included considering how I might have compromised the “immersive” element of the “immersive learning experience” that the Project on Lived Theology is meant to be.

From the moment that my summer plans came into being I began preparing myself for the mental schism that would result from living in one place and working in another. I touched on the differences between these two communities, one affluent and the other underserved, in my first blog post and I haven’t stopped being aware of them since. But, like anything else, this daily shift in my surroundings became routine. I grew comfortable. I’ve lived in relatively well-off communities my entire life, so it wasn’t hard to let myself do it again. But what I’ve learned from this experience is this: when it comes to community development, working and living in the same place is a necessity. Truly committing oneself to community development requires becoming a part of that community. I must remember that the change-makers are already living in the Tenderloin, many having lived there for their entire lives. They are entrenched; they’re bound to the people and the space in a way that I can’t replicate. If I want to come alongside them it will require being similarly bound. Only when the problems of the community become my own problems, when the community’s successes become my own successes, and my quality of life is inextricably linked to the lives of those around me, only then will I be able to serve the community well. In essence, I can’t be a commuter-developer.

Now, this is the ideal. I’m not sure if it’s always possible over the course of a lifetime but I’m positive that it is not possible within a period of ten weeks, no matter where I’m living. Also, this is not what’s expected when the Project on Lived Theology says that they encourage “immersion.” Immersion for such a short period is meant to be a taste of what living and working in a community like this could be like, along with an opportunity to reflect on the experience theologically. So even though I did not live in the Tenderloin, I tried to take in a taste of what life there could be like.

When it comes to being involved in the neighborhood, the leaders of YWAM San Francisco, Karol and Tim Svoboda, are excellent examples to follow. After spending over 20 years in India, Karol and Tim have spent the last eight years living in San Francisco and plan to be there indefinitely. Tim has an indefatigable passion for researching and learning about the neighborhood and its history. He is also a part of Market Street for the Masses, a coalition combating gentrification in the Tenderloin. He laments the entry of restaurants and other businesses, with prices well beyond affordable for most Tenderloin inhabitants, designed solely to cater to wealthier people in nearby neighborhoods. He consistently emphasizes that gentrification includes psychological displacement of a people as well as physical, and that combating it means preserving cultures, not just low-income housing.

Tim’s wife Karol is equally involved in the life of the neighborhood. She was recently invited by the former Chief of Police in the Tenderloin to be a part of a coalition for a safer neighborhood that consists entirely of Yemini women that Karol has befriended, and Karol herself. From my own experience with the Yemini community in the Tenderloin I can see that they are a tightly-knit group. It speaks volumes that Karol was given this position. She was also invited to break Ramadan with some of her Muslim friends and to attend a young Mexican girl’s first communion in the Catholic Church (alongside other BJM staff) this past summer. This, to me, epitomizes living in community; Karol, and all the staff of BJM, have taken the opportunity to “rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep” (Romans 12:15).

Early in the summer I was invited into a similar moment of rejoicing and weeping. It was a Friday morning and all of BJM staff was gathered together in the Well, our community center on Ellis Street. The Well had recently flooded and we were standing in the re-construction zone praying for the renovation process when two women, Lisa and Myra, passed by the open doorway. Lisa is one of BJM’s “cornerstone women.” She has been a friend of BJM’s since its beginnings and her story is incredible. (I encourage you to read it here in her own words.) When the pair saw all of us standing in the Well they rushed over to inform us that Lisa was on her way to the hospital – she had received a call that very morning telling her that they had found a kidney for a desperately-needed transplant and that she would be going into surgery as soon as possible. Lisa had been on dialysis for years and the team had been praying for a kidney for just as long. I’ve rarely seen such joy as I did in that room that day. There were looks of bewilderment, followed by shouts of excitement and tears of joy. Everyone rushed to overwhelm Lisa with hugs. She had to run to the hospital, but we quickly prayed her out the door, yelling over the noise of a jackhammer from the street.

In this moment I felt privileged to be a part of the team. I saw the tears streaming down their faces and I realized that these women and girls aren’t just projects to them. As Bonhoeffer says in his classic Life Together, “It is only when he is a burden that another person is really a brother and not merely an object to be manipulated” (100). Lisa is a sister to the women of BJM. They have taken on her burdens as their own. Thus, when they heard the news it was like a heavy weight had been lifted from their shoulders.

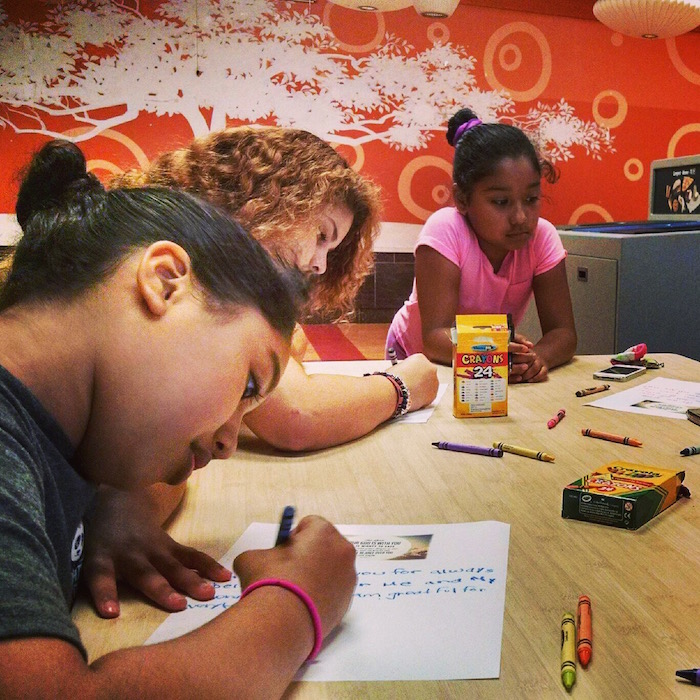

This experience inspired me to ask, what does it mean to take on another person’s burdens? Does it mean providing something constructive to benefit another person, like humanitarian relief or social services? Or does it simply mean listening and empathizing, allowing the problems of another human being to come close enough to feel them yourself? Can we (or should we) do one without the other? As I thought through these questions (to which I have no perfectly-packaged answers), I was reminded of another moment in Life Together. In his comparison of human community and spiritual community, Bonhoeffer says “… in human community, psychological techniques and methods [govern]… service consists of a searching, calculating analysis of a stranger” but in the spiritual realm “the service of one’s brother is simple and humble” (32). Although many of the women BJM interacts with do need services, whether psychological or otherwise, they need not be treated as strangers. And thus, with my limited skills as an undergraduate, all I could do this summer was treat them like neighbors. The only service I had to offer was simple and humble. I listened to women as they described their struggles–things like finding permanent housing, dealing with transphobic relatives, caring for an elderly parent, or trying to earn a college degree as a homeless student. I listened to a young girl admit that she had run away from home because she felt like no one wanted her there. I listened. I served coffee. I pushed children on the merry-go-round. I played card games. I laughed and I ran and I sat and I prayed. Most of the time that was all I could do.

As I transition back to my life as a student in Charlottesville I’m considering what it would mean to bear other people’s burdens in my community here, especially beyond my immediate circles. The UVA community faced many challenges last year, including the death of second year student Hannah Graham, the aftermath of the Rolling Stone article “A Rape on Campus,” and Martese Johnson’s assault by ABC officers. The idea that I could possibly bear any of these burdens, especially as a white student who is neither a friend of Hannah’s nor a survivor of sexual assault, seems both daunting and presumptuous. Even when I think of my own friends and the difficulties in their lives, I am faced with feelings of inadequacy. How could I possibly bear their burdens? What do I have to offer? As much as I want to see their pain alleviated, I am powerless to do so.

But that’s when I remember, bearing your sister’s burden does not require solving her problems. It does not even mean removing the burden from her shoulders. It simply means listening and serving, simply and humbly.

If you walk through the doors of the building where I work on a Monday afternoon a woman named Kimmie* will undoubtedly greet you. She will probably be wearing her trademark rainbow fedora, leggings beneath jean shorts, and something hot pink. She’ll take a pink earphone out of her ears and you’ll hear pop music blaring as she introduces herself. Then she’ll want you to meet Mama J (also known as Julia), a BJM staff member and something of a surrogate mother to Kimmie. When Kimmie found housing earlier this month (a literal miracle in the Tenderloin), she immediately called Julia and they rejoiced together. Julia even gathered the BJM staff together to host a house-warming party for Kimmie. I felt privileged to attend this party and to be welcomed into Kimmie’s home after helping carry a few gifts there.

If you walk through the doors of the building where I work on a Monday afternoon a woman named Kimmie* will undoubtedly greet you. She will probably be wearing her trademark rainbow fedora, leggings beneath jean shorts, and something hot pink. She’ll take a pink earphone out of her ears and you’ll hear pop music blaring as she introduces herself. Then she’ll want you to meet Mama J (also known as Julia), a BJM staff member and something of a surrogate mother to Kimmie. When Kimmie found housing earlier this month (a literal miracle in the Tenderloin), she immediately called Julia and they rejoiced together. Julia even gathered the BJM staff together to host a house-warming party for Kimmie. I felt privileged to attend this party and to be welcomed into Kimmie’s home after helping carry a few gifts there. Although some of my thoughts and opinions are still more progressive than many at BJM, somehow I know that if get on a high horse I will get knocked down. So I’ve gone ahead and taken my foot out of the stirrup. I may have read scholarly articles by trans people. I may be swimming in a sea of queer theology and academic jargon. I may even be “Safe Space” certified, but this does not mean that I know how to love trans people. Political correctness is not love. The women of BJM are teaching me how to love trans women. And Jesus is teaching us all.

Although some of my thoughts and opinions are still more progressive than many at BJM, somehow I know that if get on a high horse I will get knocked down. So I’ve gone ahead and taken my foot out of the stirrup. I may have read scholarly articles by trans people. I may be swimming in a sea of queer theology and academic jargon. I may even be “Safe Space” certified, but this does not mean that I know how to love trans people. Political correctness is not love. The women of BJM are teaching me how to love trans women. And Jesus is teaching us all.