Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.

Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.

Early in May, Nathan and I went to the jail to get our final okays on instituting our project at ACRJ. Neither of us had ever met Miss Vesta before. Half an hour early, we sat quietly in the purgatorial lobby.

“What’s she like?” I whispered.

“Like what?”

“Like, nice. Is she nice? Cause if she’s defensive or closed or…I don’t know. If she’s a jerk, essentially, if she’s a jerk this is going to be hard.”

“Yeh,” Nathan chirped. “I hope she talks.”

A wall of white cinderblocks and tinted, two-way, bulletproof windows separates the lobby from the rest of the facility. The guard’s desk takes up most of the floor space—thick, wooden, with bulletproof glass about seven feet high. There is only one door in and out. From the lobby-side, you can barely discern the silhouette of whoever is emerging from the bulwark of ACRJ. “Miss Vesta will be out in a minute.” The guard gave a drowsy smile from behind his barracks.

In case you haven’t been able to tell from my other blog posts *hint-hint* my prose tends ever so slightly towards the dramatic and, for better or for worse, so does my personality. “Ms. Vesta will be out in a minute” cues the pit-conductor in my head to start an overture.

The curtain rising: a tinted window firmly cast into the thick grooves of an iron door. Who will come through? Our last hope! Our last hurdle! She will make or break us! She could squash our little project and dash our hopes against the rocks! I see a silhouette move towards the door. Kettledrums thunder with every step. I envision Miss Trunchbull from Matilda or the female version of Principle Skinner from the Simpsons. The orchestra grows louder. The door buzzes open. The violins ring out like sirens. I cross my fingers and mutter mantra-like Dear Jesus! make her nice, please be nice, please be nice, please be nice, please be nice.

And then she stepped into the lobby and the music came to a jarring halt, because Ms. Vesta looked nothing like I expected. Nothing like Miss Trunchbull.

“Hello! Welcome, welcome. I’m Miss Vesta.” She reached out her hand to be shaken. Hers is the first hand I shook at ACRJ.

Unlike every single one of her colleagues, she does not wear a uniform. She doesn’t look like she works in a jail. She doesn’t look like she spends everyday in a windowless fortress. She was dressed like a schoolteacher, fully coordinated: light blue cardigan, khakis, eye shadow and smile. She warmly welcomed us. Her voice and face and demeanor were comforting and bright.

Everything about Miss Vesta is inviting—everything about the prison is not. After all, jail is the place we send people. It is meant to be the bottom-regions, the inferno of American society: the cinderblock walls, the painted emblems of Virginia law enforcement, the forest-green bars, the thin cross-wires in every pane of glass. Doors open at the buzzing behest of some unseen master-brain. Every human body is uniformed by function—officer, kitchen staff, convict. None of it invites you. It holds you hostage. Host without hospitality. It is in this place that Miss Vesta plays host: to every uniformed passerby she introduces both us and our project. “This is Mr. Walton and Mr. Hartwig. They’re going to be teaching in our summer academy this June.”

But, this week, for the first time, we welcomed Miss Vesta to our classroom. As I went through the bi-weekly routine of checking with the education office—getting our class roster, the approved box of pencils—she said, “I thought I would stop into class today. To your class, I mean. Would that be…”

“That would be great!” Dear Jesus, I hope I prepared enough… “We’re reading Blue Like Jazz by Don Miller. Does that mean anything to you?”

She shook her head.

“Great! Come. It’ll be fun.”

And, whatdyaknow, half an hour into class, Miss. Vesta knocked on the giant green door and keyed herself into the classroom.

“Am I interrupting?”

“No, no. Come in.”

All the students—well, most of the students—were sketching, with their approved pencils, on the back page of the course packet. A few were, admittedly, talking about the World Cup.

One looked up from his packet and winked. “Hello Miss Vesta.”

“Hello Mr. Mars.” She took it with a practiced teacherly elegance.

“Here, Miss Vesta,” I tore a piece of paper from my legal pad. “Draw God.”

There was a moment there—after I told her to draw God—when I think she might have regretted approving our class or, at least, worried her accreditation process was lax. What else are they doing in here? Building model villages out of Popsicle sticks? But, a guest, she sat down and began to lightly draw. We watched the clock for sixty more seconds.

“Alright everyone. Let’s share.” Nathan brought the exercise to a close.

“Anyone willing to start?” No one. “Alright. Clockwise. Mr. Levi, start us off.”

Each student shared what he had drawn: the sacred heart, Jesus as a luchador, a light bulb, a glass of water. They explained why each of these meant God for them. Miss Vesta went last.

“Alright Miss Vesta. When you imagine God you see…”

On her page was only a face. No body. A sort of androgynous, juvenile face—smiling. I wondered for a second whether she had subtly admitted to us that God, for her, was Justin Bieber or visa versa. Lifting the portrait up before the rest of the class—12 convicts who were, for the moment, her colleagues—her eyebrows arced bashfully upward.

“It’s a face. There’s…there’s its smile. I don’t know, I just, just, think of God as not really anyone specific. Y’alls were so good. I…I just, think of God sort of like this. Happy, maybe. Nice?”

I don’t know what I was expecting from her. I guess I thought somehow her drawing would stand out; that in its form and subject, her concept of God would be easily recognizable as un-imprisoned. I expected, in so many words, that Miss Vesta would conceive of God differently. Because when she unveiled to the class a bodiless, androgynous smiley-face, I thought It looks just like the inmates’. Actually, their drawings look better. But there she sat, directly to my right, no different from the 12 convicted criminals in the room. Bashful, self conscious, directed—I could no longer see the halo that before had distinguished her as part of a higher caste.

Miss Vesta did not stay in class much longer than that. She discussed her picture, sat to hear a few minutes of discussion and then, smiling quietly, politely excused herself. She stood up from the table and, unescorted, used her own key to let herself from the room.

Peter Hartwig is blogging this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Peter and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.

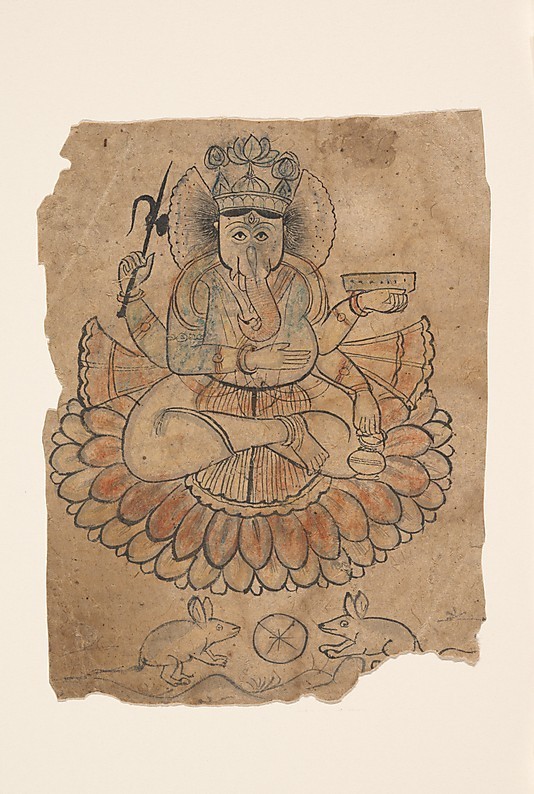

Image information:

Seated Four-Armed Ganesha

Date: ca. 1775

Culture: India (Rajasthan, Bundi)

Medium: Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Dimensions: 5 15/16 x 4 1/2 in. (15.1 x 11.4 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of Daniel J. Slott, 1977

Accession Number: 1977.440.15

http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/37928

Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.

Miss Vesta is the education director at ACRJ. She’s a godsend.

Charles Marsh, project director and author of

Charles Marsh, project director and author of