“And God said to Abram, ‘Go forth (lech l’cha)

From your land, from your birthplace, from your

Parents’ house

To the land that I will show you.’”

(Genesis 12:1)

It’s been a week since the Nazis waved their torches on the Rotunda steps in Charlottesville. A week since friends of mine, faces I have known and cherished, bodies I have stood by in the streets, put their physical safety at risk to face off against them. The day that followed was only worse, with a larger contingent of the alt-right marching through downtown, armed and aggressive, chanting racist and anti-Semitic slogans such as “Blood and soil!” and “You will not replace us! Jew will not replace us!” as they gave Nazi salutes and waved Confederate flags. It’s been a week since Heather Heyer died and other heroes were injured in the brawls. The Nazis, KKK members, neo-Confederates and other white supremacist alt-righters are, for the most part, unscathed and emboldened. Meanwhile, we have a complicit president and local institutions that refuse to do nearly enough to protect their constituents from white nationalist terror. As fires burned in the shadow of the Rotunda and blood was spilled on the streets of Charlottesville, a home to me for four of the most impactful years of my life, I was across the country on the so-called “Left” coast in Berkeley, hands tied and stomach in knots.

It was interesting, one of the first things a staff member said to me after everything happened. We were talking about my plans post-Urban Adamah, and I said that for the time being I was thinking about going back home to Virginia, to reassess my plans and figure out what comes next. He knew I was from Virginia, but I guess the conversation reminded him, and so he asked me, “Do you know Charlottesville?”

“That’s where I went to school until a few months ago.”

“Wow. Did you know people in the protests?”

“Yes.” Given who my friends are, it seems to me that any of a number of them could just as easily have been Heather Heyer.

“If you were there, would you have gone?”

“Yes.”

He smiled at me and said, “Well maybe that’s why you’re here now.” Otherwise, perhaps I’d be dead.

I guess what he said was meant to be encouraging. Out here, we like to buy into the idea that “the place you’re in right now is the exact place that you’re supposed to be.” Usually I find it helpful to think that way. And yes, I think there’s some lesson for me in experiencing all of this while so far removed from the physical space of Charlottesville. But the fact that my being here means that my body is safe from the harm that some far-right demonstrator might have wanted to inflict on it (and mine less so than others; I’m queer and Jewish and a leftist, but these are things that are harder to spot than the whiteness that so often protects me) does little to absolve the guilt I hold over the fact that I feel like I should have been there and that, yes, my body should have been on the line. Charlottesville, for all of its dark history and problematic institutions, is a home to me, and it’s where a lot of my friends are—friends who are people of color, who are women, who are queer, who are susceptible and who are targets and who are tired, physically and emotionally and spiritually, from living in a place that rejects us and being among people who want to see us dead. In all times, but especially in times like these, we need each other, and while I’m glad to be out here, I know now that for reasons that are totally outside of myself, I need to be there.

On Wednesday we went back to the Jewish Studio Project for another session with Rabbi Adina Allen, this time called “Journeying into the Unknown.” We spent a lot of time contemplating the command given from God to Abram (later known as Abraham), “Lech l’cha,” which according to the biblical commentator Rashi is both the direction to “go forth!” and to “go to you,” meant to indicate how Abram’s journey from citizen of Ur to father of a “great nation” (Genesis 12:2) would be both external and internal, at once physical and spiritual. The point here is that journeys happen on multiple levels—that transitions often bring with them transformation, as well. Coming close to the end of my time in California at Urban Adamah, I know this to be true—that the trip out here and the process of moving through the fellowship has been both a laborious physical journey and a transformative internal experience as well. It makes me wonder about the next part of my life. About what it will mean to have landed back across the country, in a place that will feel like a home and, after the events of this summer, also like someplace new and strange, and about what inner transformations await me there.

In the Genesis quote, God commands Abram to “go forth” specifically “from your land, from your birthplace, from your parents’ house.” As Rabbi Allen points out, each of these three places—“your land,” “your birthplace,” “your parents’ house”—is essentially synonymous for “home.” So then why does God basically repeat Themself? Wouldn’t “your home” or just one of these other options suffice? One possibility is that the repetition was for the sake of emphasis, to acknowledge the severity of what it was They were asking of Abram and to point out the difficulty and discomfort that comes with leaving your land, your birthplace, and your parents’ house. What the passage is getting at here is that “journeys” of the type being discussed—the kind that engender transformative experiences—are difficult, will cause discomfort, and will involve a degree of personal sacrifice. Thinking about what comes next for me and my journey, this has some resonance as well.

I’m at a point now where I don’t know exactly what comes next. Where will I be, what will I be doing a month, two months, more down the line? At this point, I think I’m okay with not knowing. “Not knowing” is something that Urban Adamah has helped me to become a lot more comfortable with than I was before. But at the same time, it helps to focus on the few things that I do know. Among them, the fact that, whatever I do and wherever I go, I want to be a positive presence in the environment around me. I want to make a difference. This can be difficult and uncomfortable, as Jewish tradition promises that our lives’ journeys will be. And of course, Judaism has something to say about being a force for positive change, as well.

The concept of tikkun olam (“repairing the world”) isn’t new to Judaism, but it has adopted new meaning in recent decades. The original meaning, as pointed out to me by my theological mentor, Rabbi Vanessa Ochs, and corroborated by the essay “Tikkun Olam in Contemporary Jewish Thought” on the website myjewishlearning.com (excerpted from the chapter “Tikkun: A Lurianic Motif in Contemporary Jewish Thought” by Dr. Lawrence Fine) had to do with the displacement of idol-worship in favor of the One God of Israel, a particularly militant and proselytizing notion. In much of the contemporary Jewish world, however, as Dr. Fine points out, “’tikkun olam’ (‘repairing the world’) has come to connote social action and social justice work” (“Tikkun”).

In the body of his essay, Dr. Fine tracks the development of tikkun olam from a concept originating in Lurianic kabbalah (a particularly potent and prolific branch of Jewish mysticism) having to do with the “repair of divinity” to the modern interpretation of it as having to do with a “mending of the world.” He points out the stark contrast in these goals by indicating the difference in the way that their “achievement” is framed. For the first, the goal is “dissolution” in the sense of a “dissolution of the material world in favor of a purely spiritual existence, similar to that which existed before intra-divine catastrophe and human sin.” This is meant to be achieved through the elimination of idol-worship. In the second framing, the goal is to “[repair] the condition of the world” through “social, moral, or political activism.” In both instances, however, Dr. Fine points out two similarities: first, that there is some “rupture” involved in the state of things that is meant to be mended, and second, that there is a large degree to which human beings are responsible for that mending process (“Tikkun”). Given the events in Charlottesville a week ago and the recurring tragedies that are becoming more and more a part of daily existence in the contemporary world, I think it is easy to see that there are social, physical, emotional, and spiritual ruptures in our times. For me, figuring out how to be a part of mending those wounds is what takes me forward, is my own “Lech l’cha.” May it be a journey of peace, if not of ease.

For updates about the PLT Summer Internship, click here. We also post updates online using #PLTinterns. To get these updates please like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter at @LivedTheology. To sign up for the Lived Theology monthly newsletter, click here.

On Bonhoeffer’s Two-Kingdoms Thinking

On Bonhoeffer’s Two-Kingdoms Thinking

Current events in American social spaces, including the recent white supremacy rallies of August 11 and 12, have made loving your neighbor a difficult undertaking. Named in honor of civil rights activist John M. Perkins, The Perkins House has been established in Charlottesville’s 10th and Page neighborhood to commit to this endeavor. Its mission is to give undergraduate students the opportunity to live in a mixed-income, multi-ethnic, and inter-generational neighborhood to prepare them for a lifetime of incarnational ministry and community partnership.

Current events in American social spaces, including the recent white supremacy rallies of August 11 and 12, have made loving your neighbor a difficult undertaking. Named in honor of civil rights activist John M. Perkins, The Perkins House has been established in Charlottesville’s 10th and Page neighborhood to commit to this endeavor. Its mission is to give undergraduate students the opportunity to live in a mixed-income, multi-ethnic, and inter-generational neighborhood to prepare them for a lifetime of incarnational ministry and community partnership. “This house will be a group of young people trying to live out an authentic faith, following the great commandment of loving God and loving each other,” Perkins said. “In this world today, there is so much division and violence, and it has been my life’s effort – and that of my wife and many others – to live a life of love.”

“This house will be a group of young people trying to live out an authentic faith, following the great commandment of loving God and loving each other,” Perkins said. “In this world today, there is so much division and violence, and it has been my life’s effort – and that of my wife and many others – to live a life of love.”

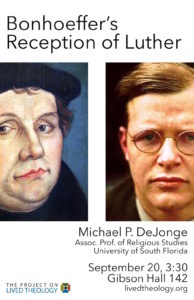

The 2017 Summer Interns in Lived Theology will give their final presentations on Tuesday, September 26 at the Bonhoeffer House, located at 1841 University Circle in Charlottesville. A reception will begin at 7 p.m., and the presentations will begin by 7:30. The public is invited, and admission is free.

The 2017 Summer Interns in Lived Theology will give their final presentations on Tuesday, September 26 at the Bonhoeffer House, located at 1841 University Circle in Charlottesville. A reception will begin at 7 p.m., and the presentations will begin by 7:30. The public is invited, and admission is free. Megan Helbling

Megan Helbling Sarah Katherine Doyle

Sarah Katherine Doyle Joseph Kreiter

Joseph Kreiter Encouraging Believers in the Wake of White Supremacy Rally

Encouraging Believers in the Wake of White Supremacy Rally On Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther

On Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther