It was an ungodly hour. I pried myself out of bed at 5:15 AM, caught the train at 6:03, and finally plopped myself down into the last row of chairs in the room. It was the dreaded 8 AM YWAM Staff Meeting. I ran my fingers through my windswept hair and willed my eyes to stay open as I looked at the title of the PowerPoint presentation that was about to begin: “Evangelism and Spiritual Warfare.”

Oh boy.

As I’ve expressed before, YWAM San Francisco is a diverse organization. Its staff is comprised of people from various age groups, nationalities, and denominational backgrounds. In each of these meetings many different “thought-worlds” collide. In other words, it’s a lot to handle at 8 AM when I haven’t yet had my coffee.

I’ve never had a very strong sense of the negative end of the spiritual spectrum. I grew up around talk of “binding the Enemy,” telling the Devil that he has “no authority here in the name of Jesus,” and the like, but I cannot claim to have any firsthand knowledge of demonic activity. I’ve heard it said that some people are just “sensitive to these things” and that I’m not one of them. (Honestly, that’s fine with me). After taking a touristy-tour of famous Buddhist temples in Bangkok, some of the people in my group reported feeling really “heavy” feelings of “darkness.” I thought I was just having a neat cultural experience. Little did I know. In Indonesia, a missionary told me that every time he heard the Call to Prayer it was like hearing the Devil remind him that he has a hold on the entire nation. I thought I was just hearing minor tones. Once again, little did I know.

The missionary teaching, however, seemed to have a keen sense of the demons among us. He doesn’t see them, he told me, but he has had first hand experiences with them. He told story after story of demons attempting to hinder his missionary efforts. One such story featured a child who grew up in a Satanist community. She attended the Christian school where he worked and would frequently tell him about the demons that still haunted her and terrorized his school. One day she ran to his office from the girls’ bathroom and told him that there were demons in there telling the girls to have sex. He believed her and commanded the demons to leave the school and face judgment from God for their actions.

Since I heard this story I’ve been grappling with mixed feelings towards it. Although I have employed sarcasm throughout this post and displayed my cynicism to the point of self-indulgence, I actually do believe that there are such things as negative spiritual beings. If I am to believe in the existence of a benevolent spiritual being (called God) based on scripture, my interpretation of the world around me, tradition, personal experiences, my cultural upbringing, and a massive leap of faith, then it makes little sense for me to not also believe in malevolent spiritual beings. So I suppose that in the times I believe God exists I also believe demons exist. Having said that, the missionary’s willingness to accept the existence of the demons in the girls’ bathroom disturbed me.

The Church has demonized female sexuality for most of its history. The connection between femininity, sexuality, and sinfulness in Western thought traces back to the Fall, the grand entrance of sin into the world. The burden of this cosmic shift has been laid largely on Eve’s shoulders, and through her, all of womankind. Eve is known as both the weak-willed woman who succumbed to the serpent’s temptation and the lascivious temptress who convinced her husband Adam to follow suit. Pseudo-Paul cites Eve as the source of all women’s subservience to men in 1 Timothy 2:

11 Let a woman learn in silence with full submission. 12 I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent. 13 For Adam was formed first, then Eve; 14 and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. 15 Yet she will be saved through childbearing, provided they continue in faith and love and holiness, with modesty.

The phrase “saved through childbearing” is often thought to be in reference to the Virgin Mary birthing Jesus. Eve and Mary are cast in opposite roles as the Whore and the Virgin, the one who brought sin into the world and the one who’s offspring brings salvation for all. They are juxtaposed as the feminine ideal and the feminine reality in its fallen state. These caricatures are ingrained in the socio-religious psyche of the West. For example, look at this fun little piece of Renaissance artwork:

Notice Eve’s position in the lowest third of the painting, lounging seductively, naked, with the serpent (thought to be the manifestation of the Devil) slithering up from between her legs. The best part about all of this is that it’s based on a shoddy reading of the Creation story. I grew up imagining Genesis chapter 3 unfolding between only two characters: Eve and the serpent. The serpent deceives Eve, who then takes the fruit to her unsuspecting husband, thus tricking him into sinning too. When I looked back on the story in my first Hebrew Bible class, I realized just how much my understanding of the story had been impacted by the Western cultural imaginary. In the same way that we imagine the “Forbidden Fruit” to be an apple even though the text offers no details about the fruit, we have no reason to believe that Eve was alone during her temptation. In fact, the text implies that Adam was there with her the entire time, and was equally deceived, but remains silent while Eve dialogues with the serpent. “She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it.” (Gen. 3:16). This seemed so obvious when it was first pointed out to me that I questioned how I could have ever thought otherwise. Then, I remembered the sort of crap that we feed our kids in Sunday school and it all became clear. (For example, this was a favorite of mine when I was a kid. Check it out starting at 17:20.) Clearly the Church’s demonization of female sexuality was not isolated to the Middle Ages, or the Victorian Era. It continued on into the 1990s and hasn’t stopped yet.

Thus, when I heard the story about the girl raised as a Satanist, my heart went out to her. Although she wasn’t raised in the Christian church, she has clearly been subjected to similarly poisonous portrayals of female sexuality. In fact, the rest of the story (not included here) made it very clear that she was subjected to all kinds of physical and psychological abuse as a child. The missionary displayed a lot of compassion for her and seemed to be a part of her support structure at the school. However, his reaction to her demons-in-the-bathroom story only further solidified the idea that female sexuality is something to be feared and curtailed. The same demons in the boys’ bathroom might be called “natural urges” or “puberty.” I wondered, if this is where the school officials think girls’ sexual urges come from, what could the school’s sex ed. program possibly look like? What is the school doing to teach girls to make safe, informed choices about sexual activity?

In his next story, our staff meeting speaker told about being out with another missionary attempting to engage people on the street in conversations about Jesus. While his friend spoke, our speaker “contended,” meaning he prayed against the Enemy so that the other missionary would be able to succeed in her task of sharing the Gospel. While he was contending, a prostitute attempted to seduce him. He was certain that this was the work of the Devil attempting to distract them from their mission.

I was livid. Here it was again. He had turned this woman into a trope. Much like the “loose woman” featured throughout the book of Proverbs, in his mind, this woman existed only to distract him, the noble gentleman, from his godly tasks. Rather than seeing a woman doing what she must to survive on the streets, probably being exploited by her pimp–a woman his organization should be reaching out to support–he saw a pawn of the Devil. He made her into a tool, a distraction, something less than human. The thought never crossed his mind (at least not that he shared) that her appearance might have been divinely ordained. Instead, he ignored her hurt, he turned his back on her pain, and he commanded “any unclean spirits” to leave in the name of Jesus.

In all of these stories these “demons” are just distractions from the real demons among us: sexism, patriarchy, Eurocentrism, manipulation, and exploitation. In Indonesia I allowed talk of the demonic to distract me from the Eurocentric attitudes I was detecting. Wanting to be as “spiritual” as everyone else, I prayed that my heart would also break for the “lost,” that I too would hear the Call to Prayer and be disturbed. Instead, I realized I respect the Call to Prayer. I wish that a sound would go off five times a day to remind me to stop and focus my heart and mind on God. I think I’d be a better Christian if that were the case. In his quest to root out demons, the missionary perpetuated harmful narratives around female sexuality and possibly even ignored a case of sex slavery in the process. I’ve seen it happen time and time again: the Church ignores real social issues in favor of imagined spiritual enemies, quoting Ephesians 6:12 as they do it. Our battle may not be against “flesh and blood” but the “spiritual forces of evil” have come in the form of tangible, temporal realities – social evils that threaten to overwhelm us if we do not fight back in spirit and in truth.

Although I’ve been working in the Tenderloin for ten weeks now, I recently spent the night there for the first time. Before settling in for a night of long conversations, junk food, and Netflix in their apartment, my fellow interns and I made the long trek (0.7 miles) to the Trader Joe’s in Nob Hill, just beyond the borders of the TL. “Heading up to Snob Hill,” one of the interns joked. I played along: “You know you’ve reached gentrification when you reach Trader Joe’s.” But even as I said this I had to admit, I have no idea what it’s like to live in an environment where gentrification is an active threat.

Although I’ve been working in the Tenderloin for ten weeks now, I recently spent the night there for the first time. Before settling in for a night of long conversations, junk food, and Netflix in their apartment, my fellow interns and I made the long trek (0.7 miles) to the Trader Joe’s in Nob Hill, just beyond the borders of the TL. “Heading up to Snob Hill,” one of the interns joked. I played along: “You know you’ve reached gentrification when you reach Trader Joe’s.” But even as I said this I had to admit, I have no idea what it’s like to live in an environment where gentrification is an active threat.

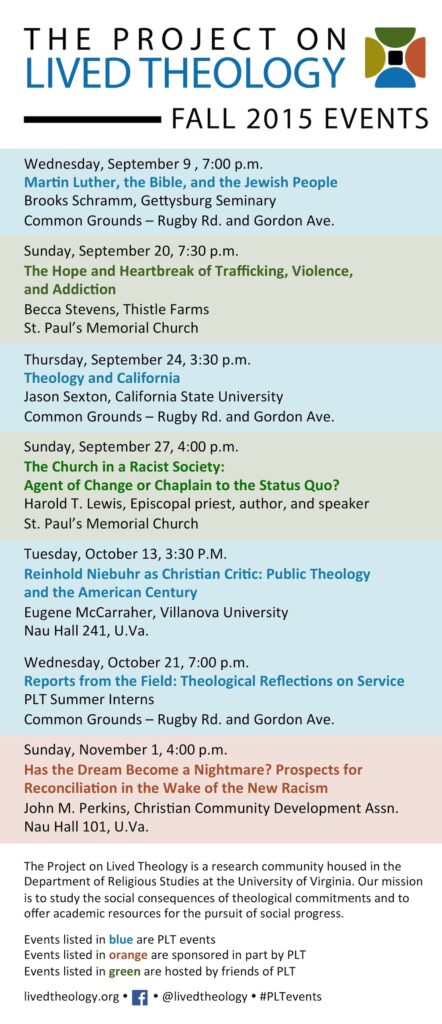

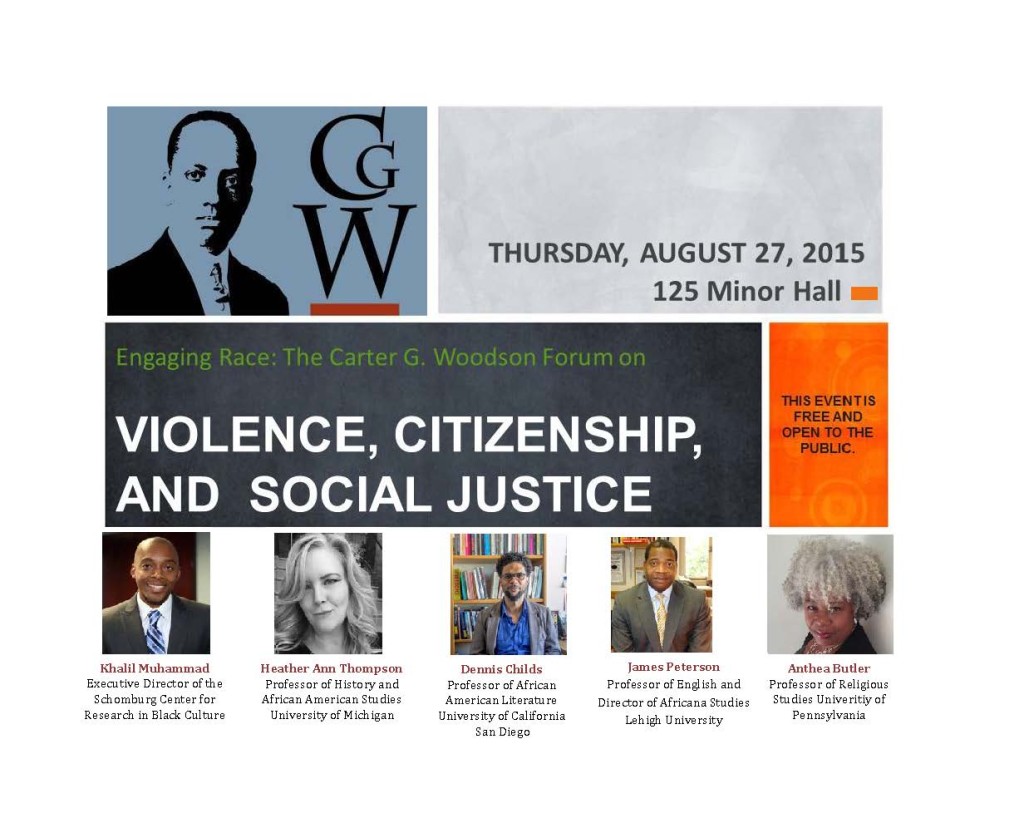

Next week, the Carter G. Woodson Institute will host a forum titled “Engaging Race: Violence, Citizenship, and Social Justice.” Anchored by Khalil Muhammad, Executive Director of the Schomburg Center in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, this forum is inspired by recent events in Charleston, South Carolina. This event is co-sponsored by the Project on Lived Theology, will be held on Thursday August 27 at 4:30 at the University of Virginia in 125 Minor Hall.

Next week, the Carter G. Woodson Institute will host a forum titled “Engaging Race: Violence, Citizenship, and Social Justice.” Anchored by Khalil Muhammad, Executive Director of the Schomburg Center in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, this forum is inspired by recent events in Charleston, South Carolina. This event is co-sponsored by the Project on Lived Theology, will be held on Thursday August 27 at 4:30 at the University of Virginia in 125 Minor Hall.