April 1, 2013 was a Monday and, like every other Monday I’ve spent in college, I spent it in Newcomb auditorium at Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship’s Monday Night Live worship service. All of Chi Alpha gets together for your average 600-person, evangelical, college fellowship meeting: we all say hi to each other until 8:05, then someone says a short ‘be quiet now’ prayer, songs, sermon, send-off, then we all say bye to each other until 9:45. Call it the Passion City model. I do not recall whether I was expecting an April Fools disruption in the liturgy; I do not recall being particularly vigilant. But in the “everyone sit down now” transition between worship song #4 and the announcements, a gorilla chased a banana across the stage.

April 1, 2013 was a Monday and, like every other Monday I’ve spent in college, I spent it in Newcomb auditorium at Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship’s Monday Night Live worship service. All of Chi Alpha gets together for your average 600-person, evangelical, college fellowship meeting: we all say hi to each other until 8:05, then someone says a short ‘be quiet now’ prayer, songs, sermon, send-off, then we all say bye to each other until 9:45. Call it the Passion City model. I do not recall whether I was expecting an April Fools disruption in the liturgy; I do not recall being particularly vigilant. But in the “everyone sit down now” transition between worship song #4 and the announcements, a gorilla chased a banana across the stage.

My friend Nick, dressed as the gorilla, chased my friend Matt, dressed as the banana, down the right aisle, across the stage and back up the left aisle. It took everyone a second to catch on. I heard gasping and laughter and then a beam of yellow struck my periphery. Matt can really move. But as he turned the left corner of the stage, the hood of the banana costume slid over his face and blocked his eyes. For some reason, perhaps the gorilla, he decided not to take the time to fix the hood and continued to run, now blind, around the corner, up the aisle and headfirst into the concrete column at the back of the auditorium.

Usually, when a crash is immanent, there’s a moment of realization, a “this is going to happen now.” Before the players collide, they close their eyes and wrinkle their mouths. Before car strikes car, the brake lights flare. Before the bomb goes off, someone yells “Get down!” But the poor banana was not afforded the luxury of that reflective moment.

Matt ran right into the pole. There was running. Then there was pain and, a second later, blood—a slight disruption in the liturgy.

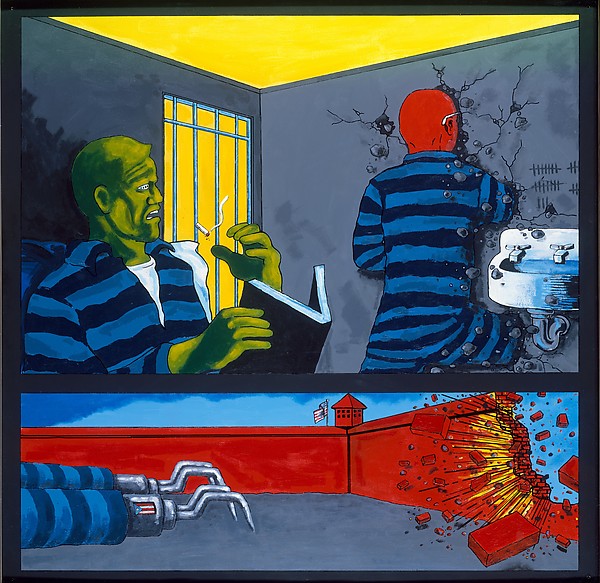

The difference between Matt and me is that when I ran headlong into the jail, I maintained a certain willful blindness. In the blog post called, Here’s How We Got Started, I talked about the moment when the idea was hatched in me to teach in a prison and about the year-long process of badgering a bureaucracy to let us into jail. Over the summer, I have had to retell the story a thousand times. “Oh, really? What an odd summer job. How did that happen?” By the end of August, it has gotten pared down to one-thousandth of its original length. “Um…I got this terrible idea to teach in a jail and someone funded it! It just worked out.”

I fear that there might be a note of arrogance in there or the glory of the victor. Veni, vidi, vici. I fear that you might hear me saying, “We did it on our own. We did it. (Well, actually I did it. Don’t tell Nathan).” I hope that is not true and that whenever the voice of pride has crept up on my shoulder, I’ve brushed off the insect.

But in retelling the story, even as it’s gotten shorter, I’ve been struck by how I was certain of uncertain things. From its conception in the Starbucks at Gibson, I believed that the project would work out somehow. And I’m not really sure where that came from or what to call it: faith or arrogance or naiveté?

As a theological point, giving “it” a name—my certainty that the project would work—means determining an object of certainty, the thing trusted-in. Faith means God; arrogance means the self; naiveté means no object, failure to consider the need for trust, failing to comprehend the possibility of failure. I am not sure if any single one of these has been true of my time as an intern. It is very possible that, in fact, the object of my trust has changed daily, or that other objects have arisen at various times.

At first, I attributed my failure to speak with theological specificity on this point to a lack of theological knowledge. “If only I’d read more Bonhoeffer I would know how to describe my summer. If only I could finish out this framework of trust, then I’d be a better blogger.” But the more I think about it, the less I think it is true—not that I am trying to let myself off of the task of theory. I am however more convinced that the problem is one of perspective.

My attempts to find and isolate the object of my trust decay into a confused navel-gazing. Counter-intuitively, the search turns introspective. I hoped to find out where it was I thought I was traveling by looking only at the direction of my feet. Instead, I’ve just got a good look at my toes. Because now that the event is over, now that we’re no longer teaching, now that we’ve actually been into the jail—I can’t imagine that the thing, whatever it is, I was trusting has stuck around, still visible and material. When I let go my fingers in relief, having gotten into jail, it feels as though the thing I held on to, like a dream, vanished.

In high school, I had read enough Jungian and Freudian theory to offer fairly entertaining dream interpretations all about guilt and sex and your parents. When I came to college that fact was leaked on my first year hall—in a momentary lapse of my own ego, I’m sure. During the fraternity-pledging season in the spring, one of the other residents came to my dorm at the end of the hall.

“You can interpret dreams?” Morpheus asked me.

“It’s not like a magical power. I just read The Interpretation of Dreams by Freud. It’s more of an intellectual exercise.”

“So in this dream, I’m just walking on the street and this guy comes up, this ugly guy. And he tells me I need to kill someone or he is going to kill me. So I just start running around trying to find someone. And I find one of the other guys in my pledge class just randomly. So I like kidnap this guy! And the cops are searching for me and they’re all after me. And I like put the kid in my basement at home. The cops are outside and I tie him up in a chair and leave him there for a whole year—it doesn’t feel like a year. But it’s a whole year. And it was like everyone had forgotten. The cops leave the house and after a year I just let him leave. He just walks outside and then I wake up.”

“How are you feeling about pledging?” I asked.

“Good. I think. I do stuff that I’d rather not do, but it’s good.” In other words, awful.

“Well, I think—and I’m not like an expert—I think it’s about pledging. I say that because of the pledge brother. So the guy on the street, the guy that says ‘unless you compromise your morals, I’m going to kill you’ would be the fraternity. Maybe you’re afraid that if you don’t pledge, you will die. Socially, you know. So in exchange for social life, the frat demands you compromise yourself. It’s important, I think, that you kill one of your pledge brothers, because he is you. If you killed one of the brothers in the frat, you would kill the frat. But instead you tie up the thing that’s most like you, one of your compatriots. You know? But you know that if you can just wait out this spring and keep everything under control that you won’t die, you won’t lose your social life. So you just keep him in the basement for a year. You don’t even kill him. Just leave him there for a little bit. And on the other side, it’s like it never happened. Except you know better than that.”

He fell eerily silent and looked at my like I was some kind of gypsy. So to try and soften the moment I said, “But, you know, if you don’t think that’s true, then it probably isn’t. Dreams are just your subconscious speaking to you, kind of. This could really all be nothing, just sort of an intellectual exercise.”

He said something like “Yeh right, haha.” And walked away. I just remember him walking away.

I don’t know what he did for the rest of the spring. I think he stuck with it. The last I saw him was at a sorority date function where he looked especially fraternal. So, I guess he just waited out the year. After all, the dream was right: on the other side of the year, the pledging season, it is all practically a dream. It’s almost like it didn’t happen. The cops leave your house. You let the pledge go. And the only person who remembers your captor-hood is you.

I feel now—now that the moment of trust is over, now that we are in the jail, now that everything will work according to the godless mechanism of bureaucracy—as though I have the answer to the question for which I was trusting. We are already sailing. And searching for that original object of our trust would be like searching for an anchor at the bottom of the sea. We are cut loose now.

I do not like this position, this self-centered, self-focused orientation. Without the externality of a trust-object, I feel like I am the only fossil I have to examine. It feels like my perspective is quite small. It is perfectly fit to the shape of my own very self. A shroud the exact shape of my world is blinding me.

The problem with my perspective is that it is mine. So, how do I get out of it? Running headlong up the aisle, blinded by my own costume, eventually I might hit the pole. Hopefully, harshly, hurtfully, and without the luxury of the reflective moment, I might just bust my skull on the pillar of the jail. But, it is, I think, worth the moment of pain.

Peter Hartwig is blogging this summer for the Summer Internship on Lived Theology. Learn more about Peter and the internship program here, and read more internship blog posts here.

Image information:

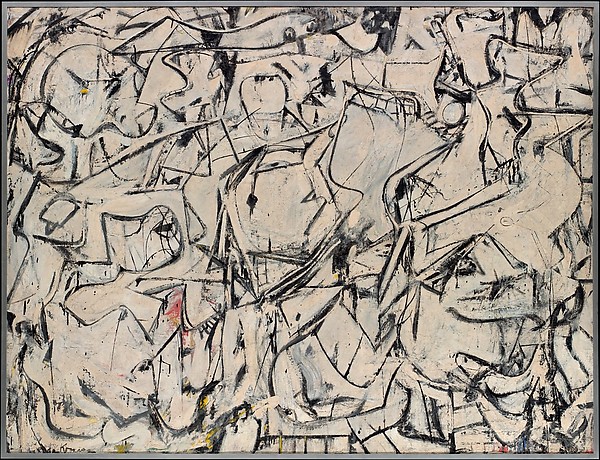

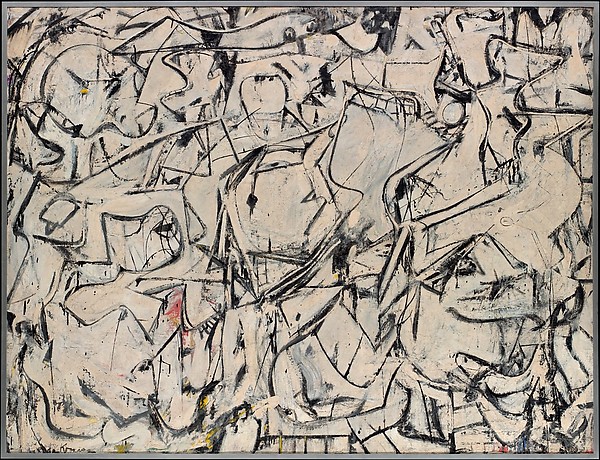

Attic

Willem de Kooning

(American (born The Netherlands), Rotterdam 1904–1997 East Hampton, New York)

Date: 1949

Medium: Oil, enamel, and newspaper transfer on canvas

Dimensions: 61 7/8 x 81 in. (157.2 x 205.7 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: The Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman Collection, Gift of Muriel Kallis Newman, in honor of her son, Glenn David Steinberg, 1982

Accession Number: 1982.16.3

Rights and Reproduction: © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/482491

Virginia Seminar member Susan R. Holman was recently interviewed by “The Poor in Spirit,” a theology blog written by Alvin Rapien. She discusses her influences and current literary interests, as well as her perspective on Christian responses and approaches to human poverty and suffering, a subject she has expanded upon in several of her books.

Virginia Seminar member Susan R. Holman was recently interviewed by “The Poor in Spirit,” a theology blog written by Alvin Rapien. She discusses her influences and current literary interests, as well as her perspective on Christian responses and approaches to human poverty and suffering, a subject she has expanded upon in several of her books.

On Wednesday, October 1, the Project on Lived Theology summer interns Claire Constance and Peter Hartwig will share their field reports, a composition of experiences gained through the PLT internship program.

On Wednesday, October 1, the Project on Lived Theology summer interns Claire Constance and Peter Hartwig will share their field reports, a composition of experiences gained through the PLT internship program.

On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

On Wednesday, September 24, Paul M. Gaston, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Virginia, will lead a seminar on the Civil Rights Movement in Charlottesville, Virginia. The seminar will begin at 3:30 pm in the University of Virginia’s

On Wednesday, September 10, Project director Charles Marsh will speak on his biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at

On Wednesday, September 10, Project director Charles Marsh will speak on his biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at