Contributed by guest author Marie Sutton

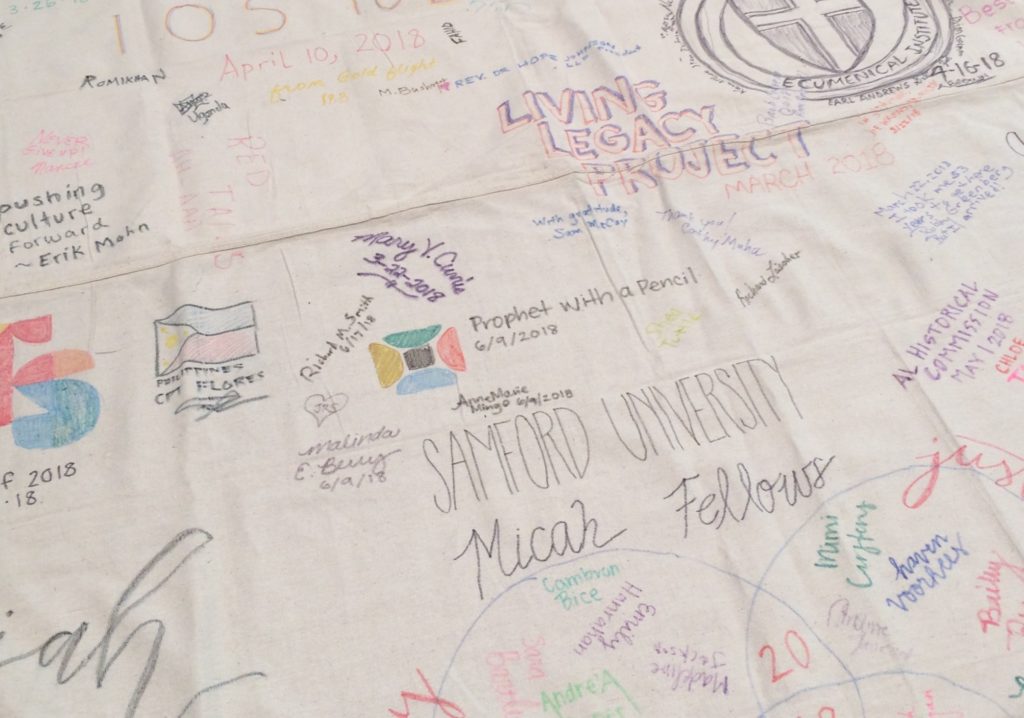

Just a few weeks after meeting the Prophet with a Pencil scholars and theologians to share her story of being jailed and persecuted for freedom, civil rights foot soldier Betty “BJ Love” King passed away.

The 72-year-old Birmingham, Alabama woman sacrificed her childhood through countless non-violent protests and demonstrations to help break the back of segregation in what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called “the most segregated city in America.” She was with the Lived Theology group in early June at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and softly spoke of the path that led her to fight segregation. She died, surrounded by her family, on June 19.

BJ Love (center) at the Prophet With a Pencil meeting

Photo by H. Jay Dunmore.

“There is a scripture that says, ‘He who has ear let him hear.’ She was one of those who heard the cry to fight against segregation,” said King’s sister Dr. E. Dashanaba King, of Ghana. And, up until her passing, King never closed her ear or silenced her call for equality and social justice for the disenfranchised.

As a 16-year-old preacher’s kid in 1963, the young woman was sitting in class at Wenonah High School in Birmingham when the “freedom bus” pulled up to recruit students to volunteer to protest laws that prevented African Americans equal access to public accommodations. While others stalled, King popped up and walked out the door.

She and others were transported to the city fairgrounds where stiff-necked policemen treated them like chattel, putting them and other children as young as 8 in cages. The young people weren’t given food and watched as their desperate parents tried to push rations through the gate. Eventually, King and the others were taken to the downtown jail where convicted criminals and thugs called home.

“She didn’t know all the fearful situations she would be getting into,” King’s sister recalled, “but she wasn’t afraid.”

King was reared by a foot soldier. Her father, the late Rev. Floyd King Sr., was an active movement man who hosted the People’s Religious Broadcast radio show and also walked alongside Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Dr. Martin Luther King.

“He would always tell us we had to do the will of God. When you feel in your heart that you have to do it, you have to do it. ‘He who has ears let him hear.’”

After being released from jail, King shared her testimony at mass rallies and church services across the city in order to help recruit other young people. And, she continued her fight against segregation, feeling the sting of water hoses and knowing the threat of being bitten by police dogs. She participated in at least 40 Freedom Rides and engaged in sit-ins and kneel-ins at white churches. She also boycotted the local library as well as countless whites-only lunch counters at restaurants and retailers. And, she was among the thousands of young people who attended the historic March on Washington.

Eventually, King and her family moved to New York. There, she took her voice to the radio airwaves alongside her father. On Sunday mornings, they would co-host a show bringing on various local choirs and gospel artists. King also shined a particularly special spotlight on what would be a fusion of gospel music and Caribbean beats that she coined, “Gospelipso.” She even penned an award-winning play called “Hallelujah New Orleans,” which was performed at the historic Cotton Club in Harlem.

In addition, King worked professionally as a certified physical therapist technician at the Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center where she got the nickname, the “singing lady with healing hands.”

“She had the biggest heart,” her sister said. “That’s why her name is BJ Love.”

Years later, King made her way back to Birmingham where she was active with social justice organizations and well as being back on the airwaves with her show “From the Mountain 2 the Valley Civil Rights Broadcast” and then later co-hosted “Great Legends in Gospel.”

In 2011, she and five other women were granted pardons for their 1963 conviction of “parading without a permit” under a city law called the Rosa Parks Act. King initiated the request and got it granted along with the other women, including her sister, Carolyn, who in 1964 integrated the all-white Jones Valley High School.

“I want her to be remembered as a lady of love,” King’s sister remarked. “Also, I want her to be known as a woman who always encouraged you to never give up. No matter your lot, if you find yourself in the fiery furnace do not give up.”

For more event details and up-to-date event listings please click here to visit the PLT Events page. We also post updates online using #PLTevents. To get these and other news updates, please like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter @LivedTheology. To sign up for the Lived Theology monthly newsletter, click here.

On the second day of the workgroup, we met at Historic Bethel Church, a National Historic Landmark and Civil Rights National Monument. The church played a central role in the civil rights movement under the leadership of Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth. In this sacred place, Prophet with a Pencil contributors delved deeper into the theology of King, focusing on his non-violent approach and the sociology of racism.

On the second day of the workgroup, we met at Historic Bethel Church, a National Historic Landmark and Civil Rights National Monument. The church played a central role in the civil rights movement under the leadership of Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth. In this sacred place, Prophet with a Pencil contributors delved deeper into the theology of King, focusing on his non-violent approach and the sociology of racism.